INVESTIGATIONS! Ananda Ehret

30°+Berlin

By: Ananda Ehret

Studio Term: SS19

Department: Urbanism and Societal Change at The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen

Published on July 23, 2021

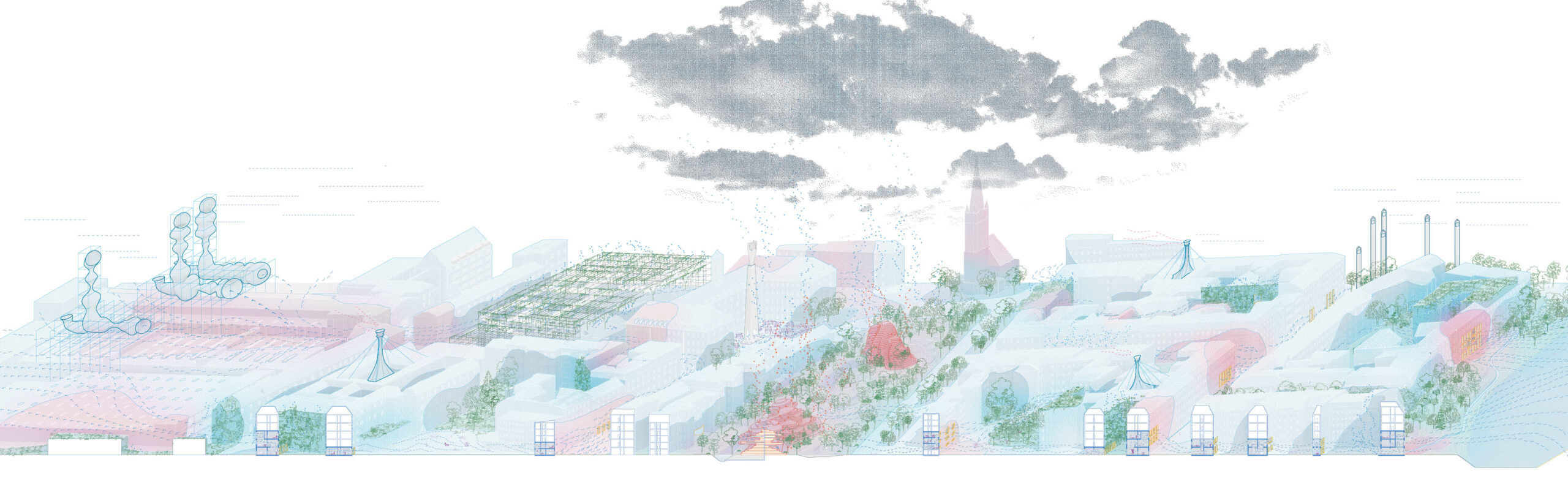

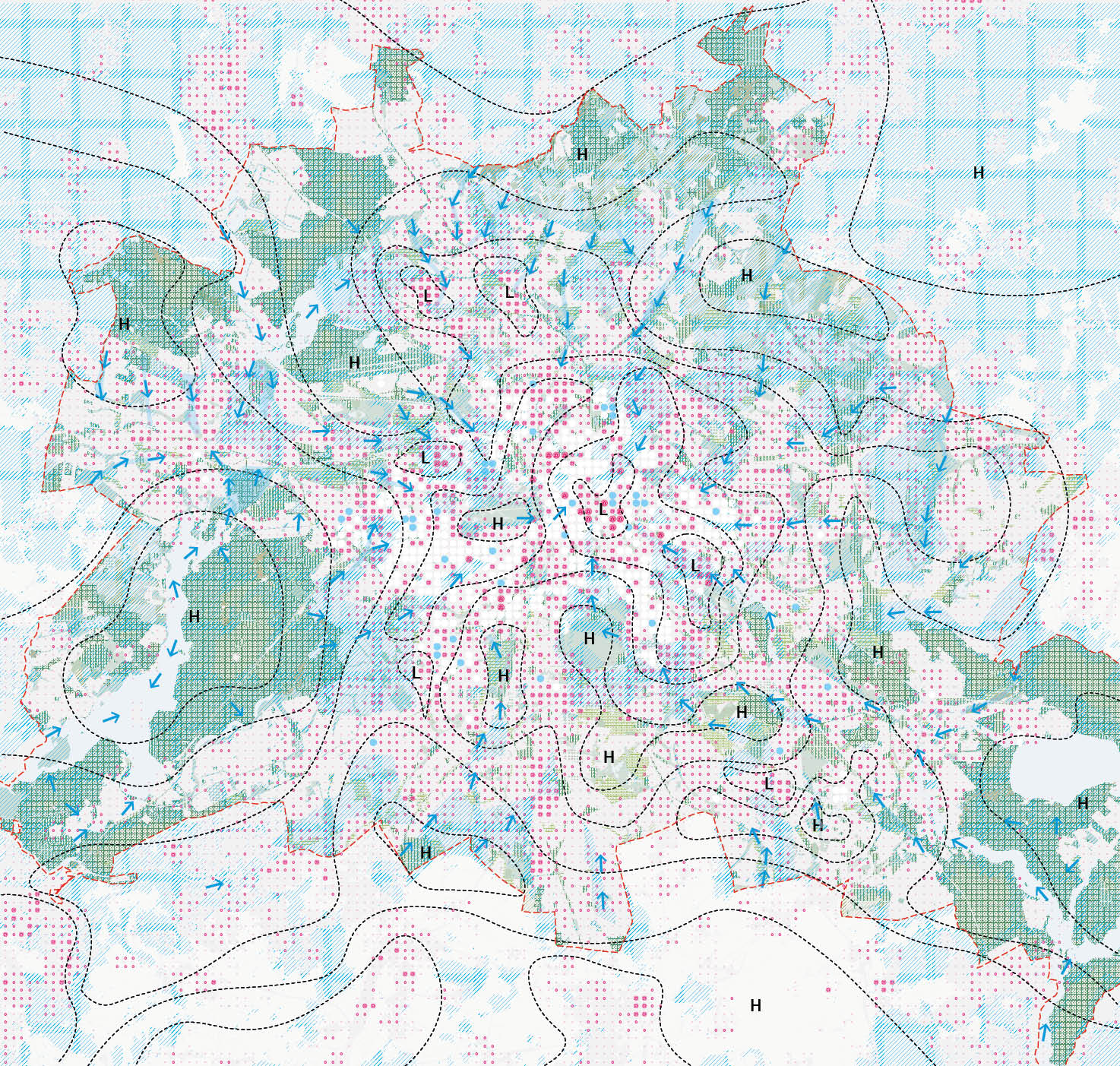

[fig 1.] The thermal strategy activates the cooling potential of existing greenspaces. © Ananda Ehret

Berlin will experience periods of extreme heat in the future. The assessment of local environmental and urban conditions facilitates effective adaption measurements

and the creation of diverse atmospheres.

Weather in Space

In the forthcoming years urban areas will be increasingly affected by the impacts of the climate catastrophe. Due to the agglomeration of people, infrastructure and economic activity cities are particularly vulnerable to these accelerating threats and therefore priority areas for climate change impact assessment. (Guerreiro et al. 2018) The Project 30°+Berlin focuses on heatwaves in the context of Berlin and explores alternative approaches for dealing with extreme heat. It aims to deploy and exploit local climatological conditions and combines temperature reduction with the creation of generous and programmed public spaces.

DEPARTMENT//

Urbanism and Societal Change / Institute for Architecture, Urbanism and Landscape /

Prof. Deane Simpson /

The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts / Copenhagen

Heat in Berlin

In Berlin, heatwaves are predicted to become more severe and frequent. Accompanied by reduced precipitation they will lead to extended periods of drought in Berlin and Brandenburg during summertime. (Zimmer-Amrhein et al. 2017) According to the European Environment Agency heatwaves are the deadliest extreme weather events in Europe. In cities the urban-heat-island-effect exacerbates these phenomenon, therefore urban residents are at especially high risk. While building materials like concrete or asphalt store heat, dense urban fabrics hinder natural ventilation during night. Furthermore, traffic and waste heat additionally increase temperatures, leading to higher energy use for cooling interior spaces and higher costs for building- and infrastructure maintenance. (Gartland 2008)

Weather in space

For centuries, climate has been of major influence for architecture and planning. Location, orientation, form and materials used to be logical consequence of local environmental conditions. In recent decades urbanization, globalization and technological advances have caused architecture to neglect the role of local climatological aspects and answers are often sought in universal solutions. (Krautheim et al. 2014) Greening the city is a trend that can be witnessed in planning proposals and architectural imagery all over the world. Green roofs and facades represent the widespread perception of a more ‘sustainable’ and ‘resilient’ urban landscape, which promises to be consistent with the planetary ecology and our individual well-being.

Referencing the notion of a “Sponge City”, planning guidelines in Berlin suggest multitude of small green spaces, trees and green roofs and facades, that reduce surface temperatures and protect from flooding. (Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Umwelt 2016) This strategy seems to be effective, when investigated on a relatively small scale; however, one must question its thermal capacity on city scale. A collaborative study by the department of architecture and urbanism TU Delft and the Shahid Beheshti University in Teheran unfolds that the cooling potential of greenspaces and trees is dependent on many additional factors. Ranging from kind and size of green spaces, demanded water supplies, air movement, humid air conditions and cost of implementations. (Venhari et al. 2017) Greening the city, the architect Philippe Rahm argues, does not reduce vulnerability, but may even exacerbate the impacts on human health. Trees could further prevent natural ventilation and keep densely build up areas from cooling down during night. (Rahm 2018) Thus, a profound understanding and assessment of local environmental and urban conditions must inform a more responsive strategy and highlight the potentials for adaptation measurements.

Microclimatic strategy in Berlin

The project 30°+Berlin was informed by vernacular architecture and a variety of contemporary interpretations that deploy thermal phenomena in relation to local circumstances. White buildings on Greek islands, wind towers in the Middle East or climate devices, designed by the architect Phillippe Rahm in the Eco Jade Park in Taiwan: diverse references show that climatic conditions and thermal phenomena interact with the build environment and natural forces can be included into design thinking. As carefully applied tools radiation, humidity, wind and ventilation broaden the scope of our action and further extend the variety of urban atmospheres.

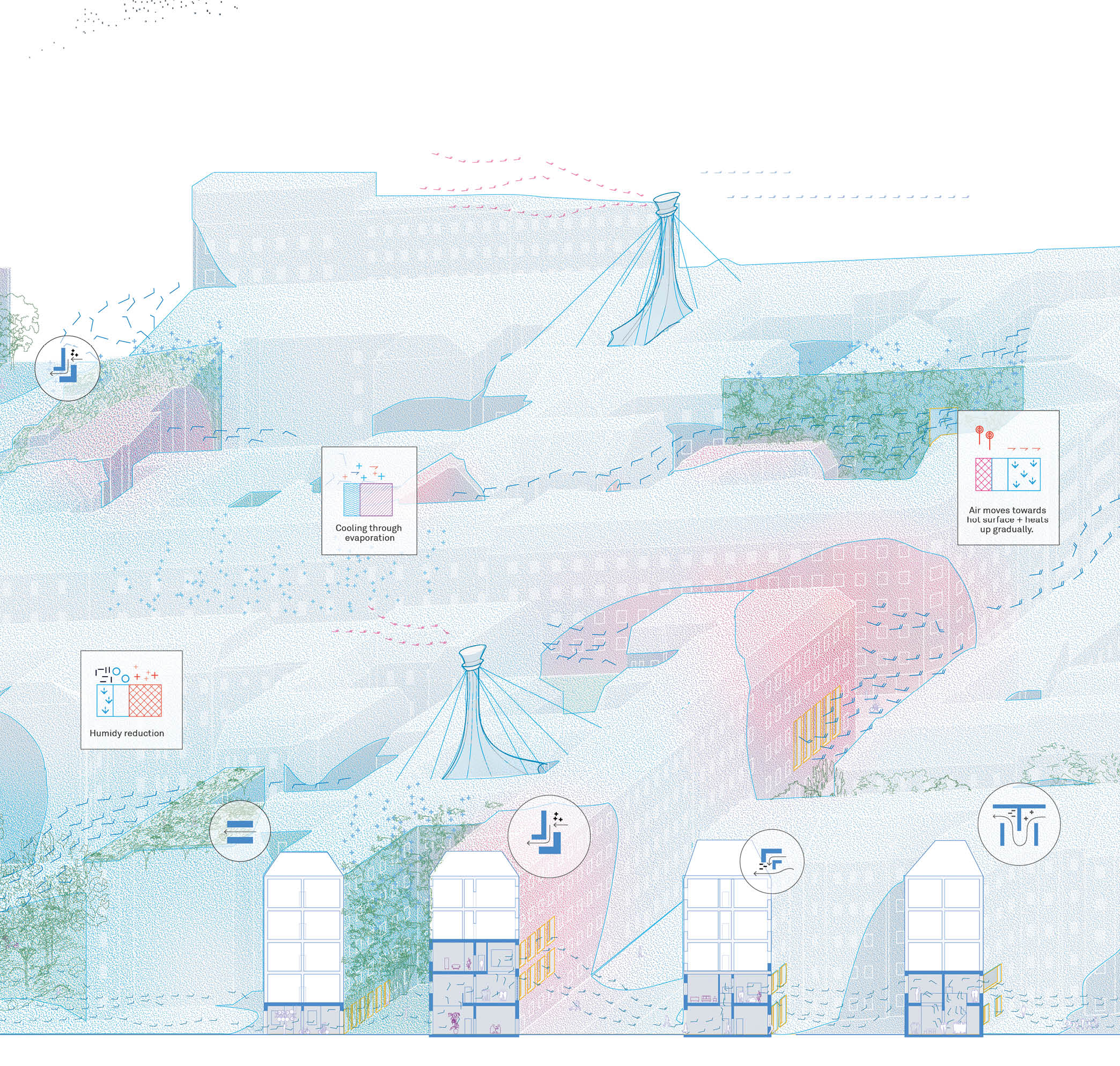

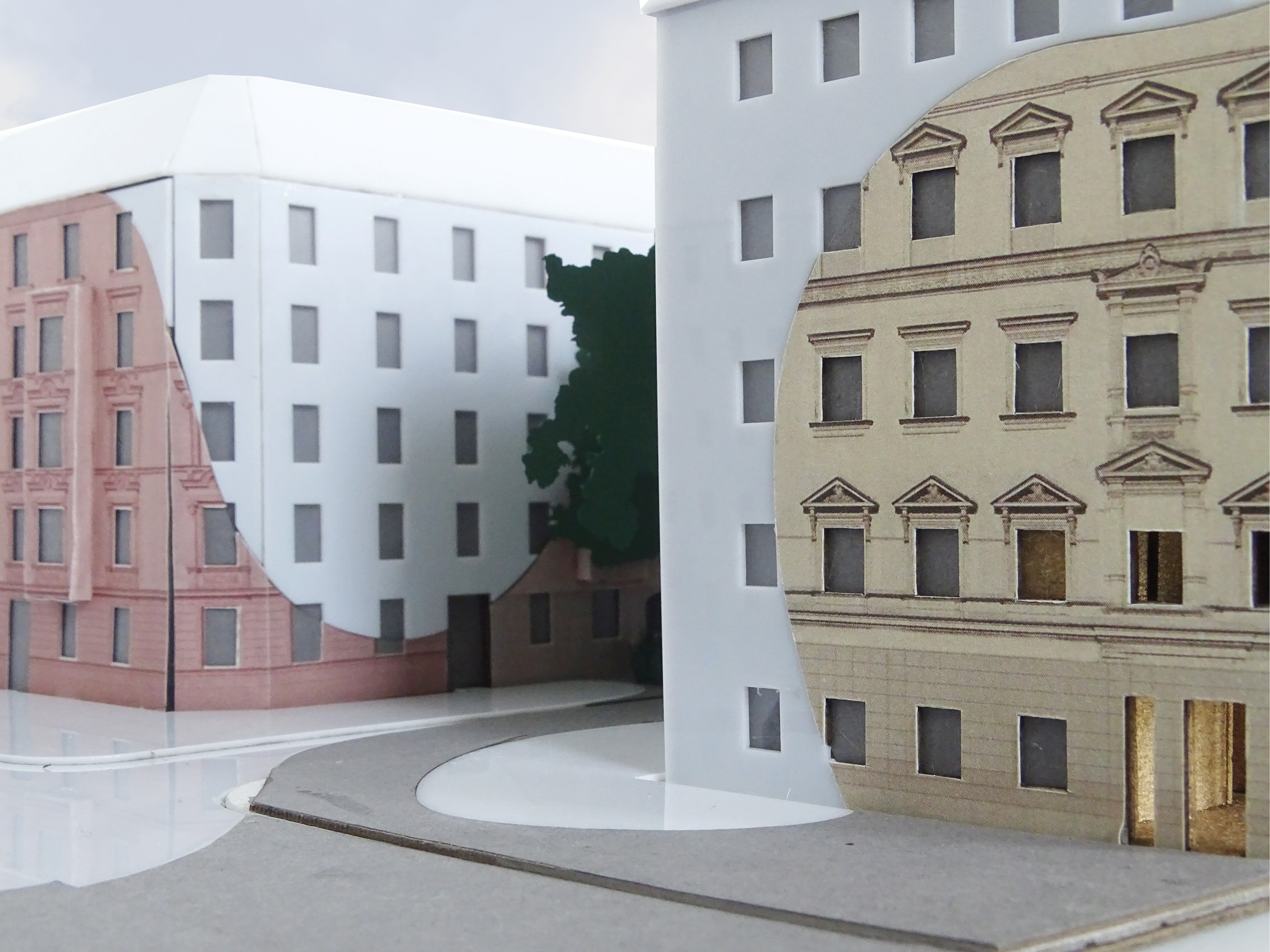

Berlin contains an exceptional number of green spaces, that make up 45 % of the urban fabric. The large spaces circulate air and can cool down urban areas in a radius of one to four kilometres. (Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Wohnen 2016) This potential is largely overlooked yet can be activated by allowing the air to access the dense urban fabric. In the Project 30°+Berlin natural ventilation is exaggerated by the design of specific surface characteristics, related air pressure differences and thermal interaction. A thick reflective layer of white paint covers large parts of roofs, streets and facades. The districts new coat reduces overall surface temperatures, while zones of darker colors form warm and even purposefully hot microclimates. Green spaces and water bodies alter the airs temperature and humidity throughout the district. Wind towers, placed as additional cold air sources, become well known meeting points to gather nearby and enjoy the cool breeze. People experience microclimatic situations differently and will choose their places of stay depending on their personal preferences and activity. During warm seasons, areas of light and reflective colours will attract public life. Green courtyards of high biodiversity invite the neighbouring dwellers and clouds of water vapour cool down the playing children’s bodies. In winter the zones of dark colours and higher temperatures will be of high popularity.

Dealing with the impacts of the climate catastrophe is a challenging design task. However, in terms of heat, there are solutions that are low-costs and relatively easy to apply. A white roof for example is 15 times cheaper than a green roof with the same thermal capacity. (Santamouris 2012) Yet, a challenging task may lay in providing a set of regulatory policies. The local government has the potential to set the strategies framework, while providing information and guidance in its implementation. Furthermore, the new policies must exceed the status of recommendation and instead become mandatory for developers and owners. At the same time bottom-up approaches can be considered. Could urban dwellers be taking care of trees and greenery? And even paint the street in front of their house?

Sources:

Guerreiro et al. 2018. Future heat-waves, droughts and floods in 571 European cities. Available at: iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/aaaad3/pdf

Zimmer-Amrhein at al. 2017. In Berliner Morgenpost. Available at: interaktiv.morgenpost.de/klimawandel-berlin/

European Environment Agency. 2017. Climate Change impacts and vulnerability in Europe 2016: An indicator-based report, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Gartland, L. 2008. Heat islands: Understanding and mitigating heat in urban area. London: Earthscan.

Krautheim, M. et al. 2014. City and wind: Climate as an architectural instrument. Berlin: DOM publ.

Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Umwelt. 2016. Stadtentwicklungsplan Klima: KONKRET Klimaanpassung in der wachsenden Stadt. Berlin.

Venhari, A. A. at al 2017 Heat mitigation by greening the cities, a review study. Tehran: Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism, Shahid Beheshti University.

Rahm, P. 2018 White is greener than green, in Domus, Volume 7, Issue 10.

Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Wohnen 2016 Umweltatlas. Berlin

Santamouris 2012 Cooling the cities: – A review of reflective and green roof mitigation technologies to fight heat island and improve comfort in urban environment, Group Building Environmental Research. Athens: Physics Department, University of Athens.

BB2040

[EN] Berlin Brandenburg 2040 was initiated by the Habitat Unit in cooperation with Projekte International and provides an open stage and platform for multiple contributions of departments and students of the Technical University Berlin and beyond. The project is funded by the Robert Bosch Foundation.

[DE] Berlin Brandenburg 2040 wurde initiiert von der Habitat Unit in Kooperation mit Projekte International und bietet eine offene Plattform für Beiträge von Fachgebieten und Studierenden der Technischen Universität Berlin und darüberhinaus. Das Projekt wird von der Robert Bosch Stiftung gefördert.