INVESTIGATIONS! Article

Urban Transformation Design — Foundations of an Urban Design Theory for the Great Transformation

By: Hişar Schönfeld

M.Sc. Urban Design. Ph.D. Candidate at Habitat Unit, Institute of Architecture, Technical University Berlin. Research assistant at the Thuenen Institute for Regional Development, Urban Designer at studio amore. Fellow of the Heinrich Böll Foundation, member of the theme cluster “transformational research”.

Published on August 12, 2020

How can a framework be developed that increases the options for action of urban designers to contribute to the Great Transformation[1] ? Based on a comparative discourse analysis at the interface of urban, transformational and design research this paper introduces the new concept of urban transformation design (UTD) and 19 hypotheses for its practical application within projects like BB2040 and beyond.

1. Intro: How can urban designers contribute to the Great Transformation?

Projects like Berlin-Brandenburg 2040 (BB2040) can be understood as both expression and drivers of a transformative turn of spatial disciplines and the emerging field of urban transformational research, exploring how urban design(ers) [2] can contribute to the so-called Great Transformation of modern society in direction socio-ecological sustainability (WBGU 2011, 2016). In the specific case of BB2040 by exemplarily investigating transformation processes in Berlin-Brandenburg from the perspective of infrastructures, asking the question how the infrastructures of Berlin-Brandenburg need to change to provide for a livable future in 2040. In the transdisciplinary research project Land*Stadt Transformation gestalten (Designing the Rural*Urban Transformation) [3] – which I am part of – we are dealing with the very similar question, how the design of rural*urban-linkages can contribute to the Great Transformation.

Both BB2040 and Land*Stadt Transformation gestalten – like many other transformation-oriented design/research projects – are hereby facing following crucial problem: Whereas there is a broad consensus in transformational science, that the Great Transformation can only succeed through active, target-oriented and effective action and this, in turn, calls for guiding transformational theories, strategies, methods and tools – to date such frameworks hardly exist. Accordingly, whereas it is claimed that the Great Transformation is decided in cities and urban designers are explicitly ascribed the responsible role of “pioneers of change” and “change agents” (WBGU 2016), to date there are no sufficient answers, how exactly they can live up to those high expectations and contribute to the Great Transformation successfully on a small scale and at the local level through the investigation on and design of the urban – respectively urban-rural infrastructures and linkages such as in Berlin-Brandenburg.

This leads me to the central questions of my paper: How can a framework be developed that increases the options for action of urban designers to contribute to the Great Transformation? How can such a framework be operationalized for and applied within projects like BB2040, Land*Stadt Transformation gestalten and beyond? This paper is aiming at developing foundations of a transformation-oriented urban design theory that increases the options for action of urban designers to contribute to the Great Transformation and which is useful for both transformational research and practice. My hypothesis is that the theoretical foundations of this framework can be developed through the interrelation and embedding of the, to date, largely disembedded fields of urban, transformational and design research and at the interface of the three concepts of an extended understanding of urbanity, a normative understanding of transformation and a political understanding of design. In order to substante this, I am going to conduct a research design that combines the method(ologie)s of comparative discourse analysis, discursive design/design for debate and mathematical set theory. By doing this, as a result, I will finally propose the new concept of urban transformation design (UTD) and conclude with a first tentative attempt for its operationalization within projects like BB2040 and Land*Stadt Transformation gestalten by proposing 19 hypotheses on the design understanding of UTD itself.

2. Research design

My research design aims at the construction of the new theoretical concept of urban transformation design, by combining the methodologies of comparative discourse analysis, discursive design/design for debate and mathematical set theory.

Comparative analysis is a method(ology) coming from qualitative social and political science that aims at the systematic interrelation of objects of research in order to formulate and test hypotheses (Pickel et al. 2009). Discursive design and design for debate are theoretical concepts coming from design research that aim to set thematic impulses and initiate academic/public debate through discursive interventions (Tharp and Tharp 2018). Set theory is a field of mathematical logic for the analysis of sets (collections of objects) which is often used in science for modelling and illustrating complex systems. Since those methodologies comprise an incoherent body of methods and aren't very systematized and because a methodological fuzziness also lies in the nature of (discursive) design itself, I take the creative leeway to combine the three approaches eclectically and to adapt them to my personal needs.

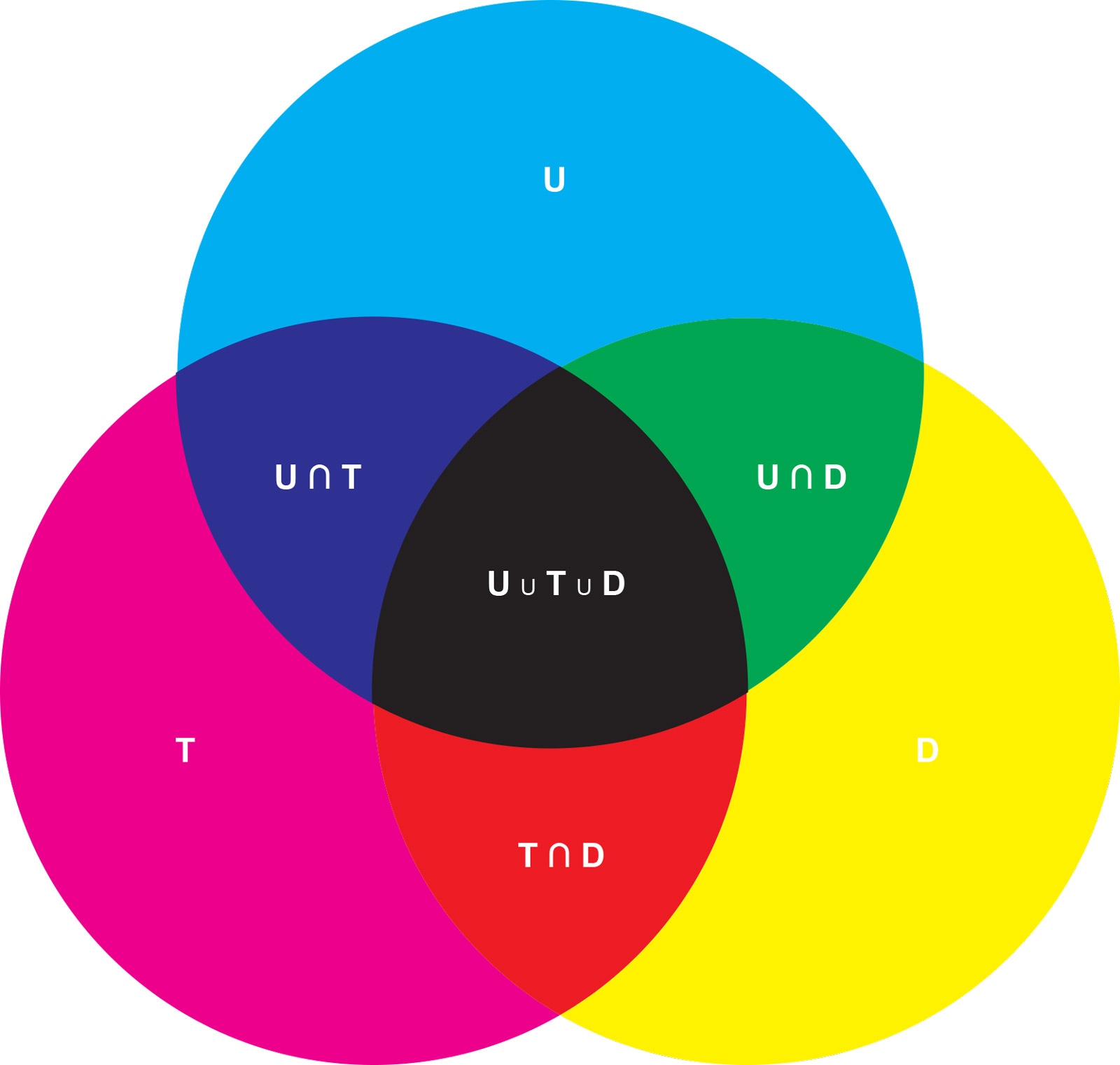

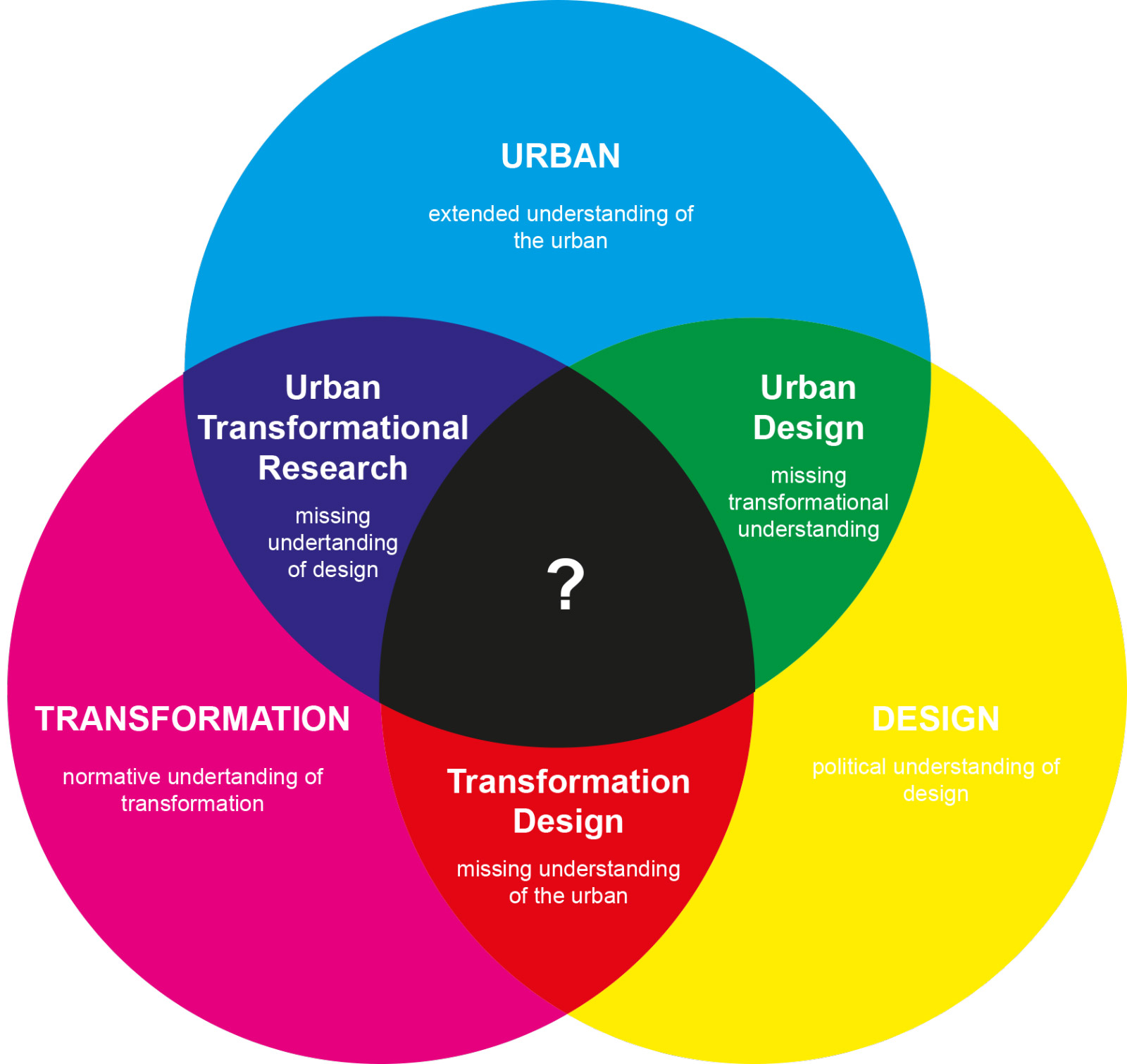

The objects of research to be compared are following three fields of discourse that I consider particularly relevant to the above-mentioned goals of this paper: urban, transformational and design research, focussing on the extended understanding of urbanity, the normative understanding of transformation and the political understanding of design, which I will summarize under the terms/symbols (U)rban, (T)ransformation and (D)esign. Since these concepts, their discursive interrelations and (dis)embeddings can be illustrated as sets, their representation and description will be based on three operators of mathematical set theory: difference set (∖), intersection set (∩) and union set (∪) (see Fig. 1). In the analysis' first step (3.1, difference set) the concepts are first going to be considered separately. The question here will be: What is the contemporary understanding of the “urban”, “transformation” and “design” today? In the second step (3.2, intersection set) they are going to be examined together, in relation. The question here will be: To what extent are the three sets (dis)embedded? In the third step (3.3, union set) research gaps are going to be derived, which result from discursive disembedding. The question here will be: How can these research gaps be solved? Finally, as a possible answer, the new theoretical concept of urban transformation design ist going to be proposed as a possible union set and as a discursive intervention.

[fig. 1] Schematic representation of the research design. Since the objects of investigation (u)rban, (t)ransformation and (d)esign can be illustrated as sets, the representation of the comparative analysis and discursive design is based on three operators of mathematical set theory: difference set (∖), intersection set (∩), and union set (∪).

3. Discourse analysis/discursive design: (U)rban, (T)rans-formation, (D)esign

3.1 U∖T∖D – Difference set, or: discourses considered separately

Aiming at the development of a framework that increases the options for action of urban designers to contribute to the Great Transformation, three fields of discourse seem particularly relevant: urban, transformational and design research. The fact that these interrelate at least partially is already evident in the sheer existence of urban transformational research itself. Nevertheless, for analytical reasons, the three objects of investigation will initially be considered separately by asking: What is the contemporary understanding of the “urban”, “transformation” and “design” today?

(U)rban – extended understanding of the urban

While spatial disciplines traditionally equate the urban with the city, today it is increasingly seen as a process that encompasses the entire planet, including the countryside, and therefore understood in an extended way (Brenner and Schmid 2014).

In this view, in the “urban age” of the 21st century, the urban is a global process. The seemingly unlimited growth of the urban and the increasing thickening of global flows of materials, goods, capital, people and communication are accompanied by a functional integration of the hinterland and an end of the wilderness. What used to be called "nature" and "the countryside" today is therefore multi-dimensionally and trans-locally interwoven with the socio-economic transformations of planetary urbanization processes and transformed into operationalized landscapes. The entire planet is urbanized. The urban, accordingly, is everywhere (ibid.).

This results in a reassessment of analytical categories and objects of investigation of spatial disciplines (Wieck and Giseke 2018). Under the influence of paradigms like the anthropocene, planetary urbanism, urban political ecology and systemic research approaches such as actor-network-theory and urban metabolism research, traditional spatial concepts such as the city and the countryside are increasingly being complemented and replaced by hybrid categories such as urban-rural-linkages, which are characterized rather by relationships and less by borderlines. These should correspond to the complex interdependencies between anthropogenic and ecological systems and help to find an appropriate approach to the transformational requirements of the 21st century (ibid.).

(T)ransformation – normative understanding of transformation

In recent years, the term “transformation” has become a new guiding concept in academic and public debates on social change. It is therefore increasingly understood in a normative way, dealing with the question how modern societies can be transformed towards socio-ecological sustainability.

Thus, in a widely acclaimed report, the Wissenschaftlicher Beirat der Bundesregierung Globale Umweltveränderungen (WBGU, German Advisory Council on Global Change) called for an in-depth structural change of modern societies, which is understood as a Great Transformation (WBGU 2011). A constituent part was the demand for a new contract between science and society, which has been met with great response, was taken up and further developed within sustainability research.

For this reason, transition and sustainability research is currently being reinvented as so-called transformative science and transformative research (Schneidewind and Singer-Brodowski 2014). These designate a mode of science that actively promotes social change towards sustainability with research and education not only about, but also for the Great Transformation. They stand for a paradigmatic shift that aims to change science in direction of transformational knowledge production. In this context, science is increasingly becoming applied, problem-oriented and transdisciplinary, being understood as a normative project (ibid.).

(D)esign – political understanding of design

Two developments are shaping the world of design today: the "design turn" of non-designerly disciplines and the "political turn" of design itself.

While design research has long had a marginal and precarious position in the academic landscape (Mareis 2016), in recent years a growing interest in design can be observed. Along with a so-called “design turn” of genuinely non-designerly disciplines, the concept of design has arrived in transdisciplinary contexts between the natural sciences, engineering and the humanities as well as economics, politics and civil society. Here, design increasingly serves the communication of complex issues, the solution of problems, technical and social innovation and practice-oriented knowledge production (ibid.). Since knowledge in design often is created through reflective practice (Jonas 2010), it is increasingly recognised and accepted as a mode of science on its own.

Meanwhile, the “political turn” of design itself is leading to a delimitation and expansion of the concept and an increasing interest in its socio-political dimensions. In relation with the socio-political challenges of the 21st century, design research increasingly reflects the relation of design, society and politics by asking about ethics and responsibility and by setting normative goals. Design therefore is increasingly understood as a political practice. Accordingly, designers no longer merely design objects, but – in a broader sense – processes, interventions, images, narratives and visions of the future of society (Mareis 2016).

3.2 U ∩ T ∩ D – Intersection set, or: discourses considered together

After having looked at the concepts of the urban, transformation and design separately and showing that they are increasingly being understood expanded, normatively and politically in the first step of the analysis, we will now analyse them comparatively and focus on discursive embeddings and disembeddings, by asking: To what extent are the three sets (dis-)embedded?

Urban ∩ Transformation

Embedding – urban transformational and living lab research: Cities and urban designers play an important role in transformative science (WBGU 2016). The normative understanding of transformation of transformational research also increasingly finds its way into spatial disciplines (Knieling 2018, Brokow-Loga and Eckardt 2020, Lange et al. 2020). These interrelations of transformative science and spatial research are mainly mirrored in the emerging fields of urban transformational and living lab research (MWK 2018), as well as in the importance of cities for the methodological systematization of living lab research itself (Schneidewind 2014). However, these interrelations cannot hide the facts that the understanding of the urban within urban transformational and living lab research often falls behind the state of research of spatial disciplines, being equated with "the city" in a limited sense (WBGU 2016) and that representatives of spatial disciplines still rather understand and conduct transformation in a rather descriptive way.

Disembedding – lack of understanding of design: The main deficit here, however, is the largely disembedding of design discourses. Although (co-)design is regarded as a constitutive element of urban transformational and living lab research, to date there is little literature about what the meaning and task of design actually is or should be within this context. One important reason for this might be that, despite current approximation of science and design, in recent decades all efforts to establish design as an independent academic discipline have been accompanied by an almost indissoluble entanglement between theory and practice, between design as a scientific discipline and practical activity. Design still has a relatively precarious position in academia and still has to assert itself in distinction to established disciplines (Mareis 2016).

Transformation ∩ Design

Embedding – transformation design: The fact that transformational and design research are converging is mirrored in the new concept of “transformation design”, a relatively young field of discourse, research and practice that aims to contribute to the Great Transformation in a designerly, creative and aesthetic way (Sommer and Welzer 2014; Jonas, Zerwas and von Anselm 2016). Still, as obvious as the linkage and application of transformation design within urban transformational and living lab research may seem, it does hardly play a role here yet. Although the Great Transformation serves as a name-giver, the systematizations and methodologies of transformational and living lab research on the other hand have so far been given relatively little consideration in the conceptually still vague transformation design (ibid.).

Disembedding – lack of understanding of the urban: The same applies to the urban. While urban processes and spaces obviously are of great importance here – as examples for transformation design predominantly spatially related references are given – the literature on transformation design often falls behind the state of research of spatial disciplines, since it either (and mostly) refers to the city or (less) the countryside (ibid.). This is probably due to the fact that transformation design, like urban transformational and living lab research, is still young and little developed and applied.

Design ∩ Urban

Embedding – urban design: Since the founding of urban design in the mid-20th century in the US, there is a discipline that is explicitly and namely located at the interface of urban and design research and practice (Arida 2008). What may suggest the embedding of urban and design research and practice here is, however, only partially the case. Urban design is primarily a territory of spatial disciplines, primarily exercised by architects and usually called "Städtebau" in German-speaking countries. Other than it might seem, design and spatial disciplines have formed separate disciplinary enclaves and traditionally conduct their own, largely separate theoretical discourses (Marshall 2006). Design research therefore de facto has as little importance within the research on urban design as it does the other way around (Mareis 2016). As a result, urban designers often lack the political understanding of design to be able to contribute to the Great Transformation successfully (Sorkin 2009). In turn, (transformation) design lacks not only the (expanded) understanding of the urban, but also the spatial design skills of spatial disciplines, like (landscape)architecture, urban planning and urban design.

Disembedding – lack of understanding of transformation: More problematic here, however, seems to be the lack of "transformative literacy" (Schneidewind 2018) of urban design(ers). In view of the fact that the WBGU describes urban designers as "pioneers of change" without whom transformation is not possible (WBGU 2016), it is striking how little attention urban design has been paying to transformative research so far. The term “transformation” may be familiar to urban designers. In the discourses of spatial disciplines there is a lot of talk about the "transformation of spaces" and "spaces in transformation" (Bosselmann 2008, Ruby and Ruby et al. 2008). Nevertheless, the understanding of transformation here usually differs fundamentally from the understanding of transformational research. The transformational understanding of spatial disciplines is mostly descriptive. To date, it most commonly describes the change of socio-spatial (infra)structures without necessarily meaning a profound, in-depth structural transformation of society. Large parts of spatial disciplines therefore are – provocatively put – "transformational illiterates", in the normative sense of the word (Schneidewind 2018).

3.3 U ∪ T ∪ D – Union set, or: from discursive disembedding to embedding

The comparative analysis of the urban, transformational and design research in the second step of the analysis shows that there are discursive and practical interrelations and disembeddings. The main embeddings are most clearly mirrored 1. in the discipline of urban design, 2. in the existence of urban transformational and living lab research and 3. in the new concept of transformation design. The disembeddings are most obviously visible 1. in the lack of a political understanding of design within transformational and living lab research, 2. the lack of an extended understanding of the urban within transformation design and 3. the lack of a normative understanding of transformation within urban design.

[fig. 2] Result of the comparative analysis. There are both discursive embeddings (urban design, urban transformational and living lab research, transformation design) and disembeddings (lack of understanding of the urban, transformation and design, lack of union set) between urban, transformational and design research and practice.

These disembeddings – I believe – are both research gaps and practical obstacles for transformational action (see fig. 2). They seem to be important reasons for the lack of a framework so far. Still, with urban design, urban transformational and living lab research and transformation design, there are three existing approaches with the potential to serve as a basis for developing a framework that increases the options for action of urban designers to contribute to the Great Transformation. For this, however, to date these three approaches have not yet been systematically integrated and interrelated enough. This is the research gap. The practical obstacle to transformational action in turn lies in the open question of what and how to design.

From this – so my hypothesis continues – the following research need arises: The question how these gaps and obstacles can be eliminated and overcome. My (quite obvious) answer is: through the consistent and systematic contextualization and embedding of the three discourses and concepts where they are disembedded. For developing an urban design theory for the Great Transformation the urban, transformation and design be consistently and systematically integrated and interrelated. The transformational research on/design of urban-rural infrastructures and linkages requires all three of them: an expanded understanding of the urban, a normative understanding of transformation and a political understanding of design. In short: there is a need for a union set.

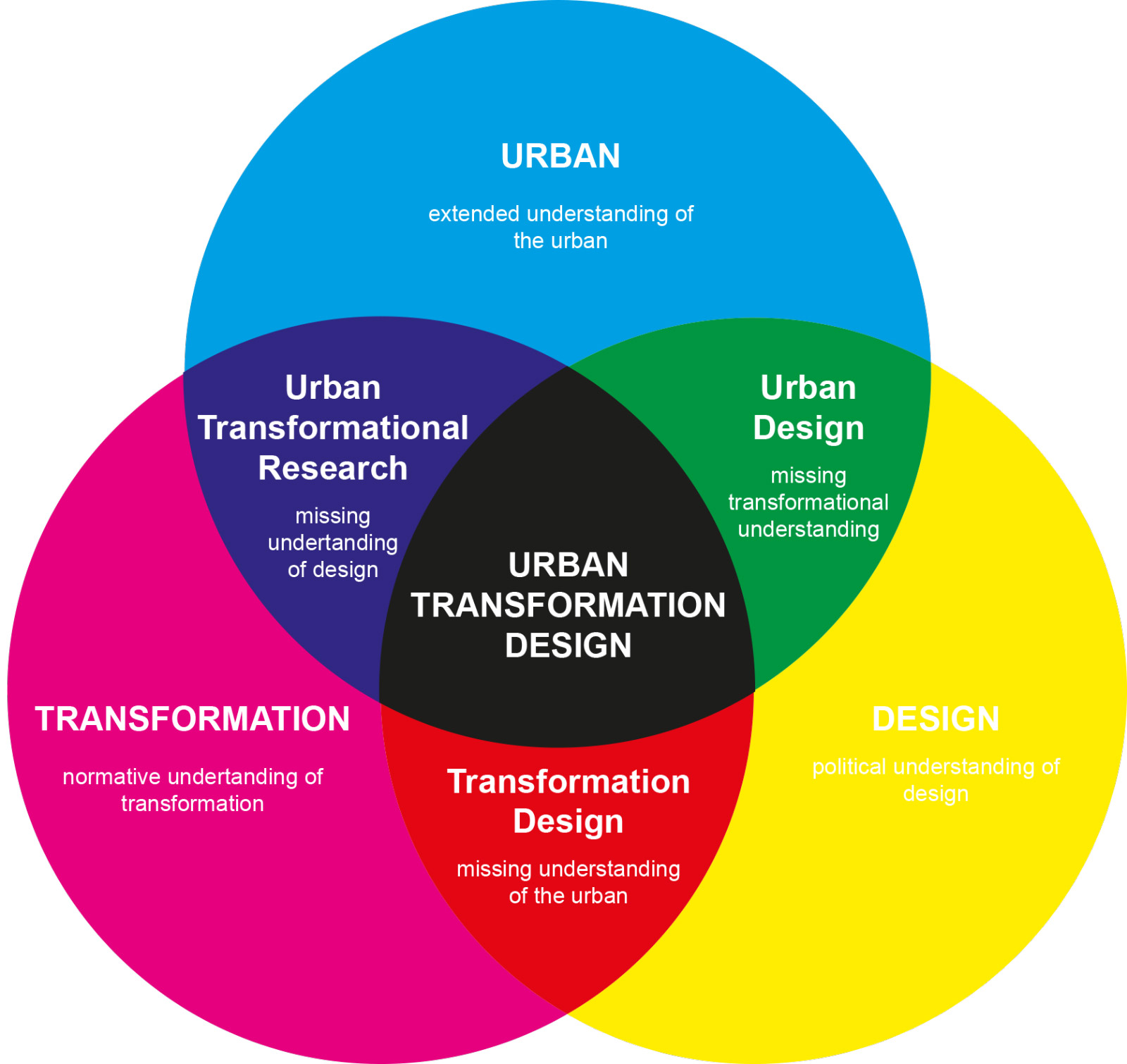

This union set, I propose, could be called urban transformation design (UTD). UTD could contribute to a threefold „Aufhebung“ of the discursive disembeddings (missing understanding of urbanity/transformation/design) in a Hegelian sense (negation, preservation and sublimation, Schwandt 2010). UTD builds a semantic bridge between the enclaves of urban, transformational and design research and opens up a productive common ground. It transcends the three disciplines and links the three intersection sets of urban transformational and living lab research, urban design and transformation design as a mediating interface.

UTD therefore is my answer to the question asked above: How can a theoretical framework be developed that increases the options for action of urban designers to contribute to the Great Transformation? It is the systematically and theoretically grounded formulation of an extended, political and transformational understanding of urban design. It is the foundation of an urban design theory for the Great Transformation. UTD is a figure of thought, a heuristic concept, an attitude, a proposition of how to think and practice urban design. It could convey the problem awareness and (self)consciousness and provide the theories, strategies, methods and tools that we need in order to contribute to the Great Transformation successfully. In this way, UTD could provide the theoretical foundations for the transformation of rural*urban-infrastructures and linkages in Berlin-Brandenburg and beyond. Herein, I believe, lies the potential – and the necessity – of UTD.

[fig. 3] Result of the discursive design. "urban transformation design" (UTD) as a discursive intervention and a proposal for a union set.

4. One step towards operationalization: the design understanding of urban transformation design

Now, having answered the first question of the paper, we can proceed to the second one: How can UTD be operationalized for transformational research and practice, in projects like BB2040, Land*Stadt Transformation gestalten and beyond?

A first tentative attempt for its operationalization might be illustrating the design understanding of UTD itself. As I proposed, UTD is based on a political understanding of design – transformation design in particular. Following the famous definition of the design theorist Herbert Simon (1996), according to transformation design everything can be regarded as design where options for action are increased in order to transform existing situations into desirable ones. The design theorist Wolfgang Jonas, who mainly coined the concept of transformation design in Germany, therefore suggests that transformation design can be understood as the most general, comprehensive and fundamental design concept, as "the new normal design" (Jonas 2018). According to this, all (political) design concepts are sub-concepts that can be derived from the basic concept of transformation design (ibid.).

As I have shown before (Schönfeld 2020) indeed a broad variety of extended and political design concepts can be consistently integrated in and subordinated to the concept of UTD. This in turn enables UTD to utilize those concepts. Therefore, as a first tentative attempt for its operationalization, by referring to the rich body of literature on political design concepts I am going to outline the (possible) design understanding of UTD with following 19 hypotheses, which might help as guidelines for its practical application in later empirical field work:

- UTD is critical design: it understands urban spaces and processes as a mirror of power relations and draws attention to socio-spatial grievances (Raby 2008).

- UTD is activist design: it acts out subversion and counter-hegemonic protest, intervenes into urban spaces and processes in order to transform them, and calls for emancipative action (Scalin and Taute 2012).

- UTD is design as infrastructuring: it aims on the initiation and support of processes of communitarisation and enables local communities to solve common problems collectively and to autonomously create social and technical innovations (Hillgren, Seravalli and Emilson 2011).

- UTD is political design: it understands the design of urban spaces and processes as a political practice and wants to exercise socio-political influence (Höger and Stutterheim 2005).

- UTD is discursive design: it contributes to discursive interventions, initiates public debates on topics of social and political relevance, sets thematic impulses and directs debates in desirable directions (Tharp and Tharp 2018).

- UTD is emergency design: it creates habitats and protection zones in the context of crisis, disaster and conflict (Milev 2011).

- UTD is entwerfendes design: it creates room for maneuver, which increases the options for action of people to transform existing (spatial) situations into desirable ones (von Borries 2016).

- UTD is experimental design: it understands urban spaces as living labs for the implementation of real life experiments: problem-oriented and open-ended processes of joint research and learning (Fezer und Banz 2016).

- UTD is gender design: it designs egalitarian spaces, which are free from stereotypical, sexist and otherwise discriminatory sexual assignments and allow a free expression of sexuality identity and desire (Brandes 2017).

- UTD is human-centered design: it designs urban spaces, in which the people's characteristics, problems and needs are the focus of attention (Hofmann 2017).

- UTD is sustainable design: it creates urban spaces that have a future (Bergman 2012).

- UTD is open design: it creates urban spaces that are accessible for and can be used by everybody, that can be co-designed, freely used and appropriated (Open Knowledge Foundation 2020).

- UTD is participatory design: it creates urban spaces together with those who live in them and who are affected by them (Simonsen and Robertson 2013).

- UTD is reflective design: it is research about/for/through/as design on urban spaces and understands this as a reflective practice that produces knowledge (Jonas 2010).

- UTD is self design: it is aware of the dialectic relationship between people and the urban – the creation of sustainable spaces creates sustainable subjects, which, in turn, create sustainable spaces (von Borries 2016).

- UTD is social design: it creates just and sociable spaces that change society (Banz 2016).

- UTD is speculative design: it creates possible, plausible, probable and desirable images of the future, narratives and spaces that mirror contemporary social conditions and contribute to the reflection on desirable futures (Dunne and Raby 2013).

- UTD is (eco-)system design: it designs urban spaces and processes, which correspond to the complexity and interdependence of the ecological and anthropogenic systems and subsystems of our planet and contributes to their stability (Stroh 2015).

- UTD is invisible design: it creates immaterial processes, relationships, experiences, atmospheres and situations that may not be directly recognizable, but subtly – and yet decisively – have a positive effect on our urban environment (Burckhardt 2012).

5. Conclusion: Research Through (Urban Transformation) Design

In the face of missing transformational theories, strategies, methods and tools and insufficient answers how exactly urban designers can live up to the high responsibility assigned to them by transformational science, this paper was asking the question how a framework can be developed that increases the options for action of urban designers to contribute to the Great Transformation and how such a framework might be operationalized for and applied within projects like BB2040, Land*Stadt Transformation gestalten and beyond.

By conducting a comparative discourse analysis, new research gaps at the interface of urban, transformational and design research were identified, which seem to be important reasons both for the lack of transformational frameworks and obstacles for transformational action of urban design(ers). Introducing the new concept of urban transformation design (UTD), both a way for overcoming and eliminating those research gaps and foundations of an urban design theory for the Great Transformation were proposed. Referring to a broad variety of political design concepts, 19 hypotheses about the design understanding of UTD itself were given, which might help as guidelines for its practical application in the context of later empirical fieldwork.

UTD, in the form in which it is presented here, initially functions as a discursive intervention. It is an attempt to intervene in the discourses of urban, transformational and design research and practice in order to stimulate reflection and discussion on what the meaning and task, the strategies and methods of urban design could/should be today. Referring to the 19 hypothesis about the design understanding of UTD itself, its theoretical foundations now could be practically applied, critically examined and further developed in the field by conducting research through (urban transformation) design, such as in the “transformation laboratories” of BB2040, within the four living labs of the project Land*Stadt Transformation gestalten and beyond.

Acknowledgement

This paper has been written in the context of the trans-disciplinary research project Land*Stadt Transformation gestalten, which is funded by the program Spielraum – Urbane Transformation gestalten of the Robert Bosch Stiftung from 2017 to 2021.

References

Arida, A. (2008). “Urban Design”. In: Erlhoff, M. and Marshall, T. (Eds.) (2008) Wörterbuch Design: Begriffliche Perspektiven des Design, 422–424. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Banz, C. (Hrsg.) (2016). Social Design: Gestalten für die Transformation der Gesellschaft. Bielefeld: transcript.

Bergman, D. (2012). Sustainable Design: A Critical Guide. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press.

Brandes, U. (2017). Gender Design: Streifzüge zwischen Theorie und Empirie. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Brenner, N. and Schmid, C. (2014). “Planetary Urbanization“. In: Brenner, N. and Schmid, C. (Eds.).

Implosions/Explosions: Towards a Study of Planetary Urbanization, 160–163. Berlin: Jovis.

Brokow-Loga, A. and Eckardt, F. (2020) Postwachstumsstadt. Konturen einer solidarischen Stadtpolitik. Bielefeld: transcript.

Burckhardt, L. (2012). Design ist unsichtbar. Entwurf, Gesellschaft und Pädagogik. Berlin: Martin Schmitz.

Bosselmann, P. (2008). Urban Transformation: Understanding City Design and Form. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Dunne, A. and Raby, F. (2013). Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

Fezer, J. and Banz, C. (2016). “Experimentelles Design. Für einen engagierten Designbegriff”. In: Banz, C. (Eds.) (2016). Social Design: Gestalten für die Transformation der Gesellschaft, 71–84. Bielefeld: transcript.

Hillgren, P.-A., Seravalli, A. and Emilson, A. (2011). „Prototyping and Infrastructuring in Design for Social Innovation“. In: CoDesign, 7(3–4), 169–183.

Höger, H. and Stutterheim, K. (Eds.) (2005). Design & Politik: Texte zur gesellschaftlichen Relevanz gestalterischen Schaffens. Würzburg: Querfeldein.

Hofmann, M. L. (2017). Human Centered Design: Innovationen entwickeln, statt Trends zu folgen. Paderborn: Wilhelm Fink

Jonas, W. (2001). “Design – es gibt nichts theoretischeres als eine gute Praxis”. Available at: http://home.snafu.de/jonasw/JONAS4-57.html [12.08.2020].

Jonas, W. (2010). “Research through Design”. E-mail-Interview on Design Research for the Chinese Journal “Landscape Architecture” and the website “Youth Landscape Architecture”. Available at: http://www.transportation-design.org/cms/upload/DOWNLOADS/20101220_Youthla-Interview_Jonas.pdf. [12.08.2020].

Jonas, W., Zerwas, S., von Anshelm, K. (Eds.) (2016). Transformation Design: Perspectives on a New Design Attitude. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Jonas, W. (2018). “Prolog”. In: Förster, M., Hebert, S., Hofman, M. and Jonas, W. (Eds.) (2018). Un/Certain Futures – Rollen des Designs in gesellschaftlichen Transformationsprozessen, 16–24. Bielefeld: transcript.

Knieling, J. (Eds.) (2018). Wege zur großen Transformation: Herausforderungen für eine nachhaltige Stadt- und Regionalentwicklung. München: oekom.

Krieger, A. (2006a). “Toward an Urban Frame of Mind”. In: Harvard Design Magazine, 24, 3.

Krieger, A. (2006b). “Where and How Does Urban Design Happen?”. In: Harvard Design Magazine, 24, 64–71.

Lange, B., Hülz, M., Schmid, B. and Schulz, C. (Eds.) (2020). Postwachstumsgeographien. Raumbezüge diverser und alternativer Ökonomien. Bielefeld: transcript.

LSTG (Land*Stadt Transformation Gestalten) (2020). Project Website. Available at: https://www.land-stadt.net. [12.08.2020].

Mareis, C. (2016). Theorien des Designs zur Einführung. Hamburg: Junius.

Marshall, R. (2006). “The Elusiveness of Urban Design”. Harvard Design Magazine, 24, 10–20.

Milev, Y. (2011). Emergency Design. Berlin: Merve.

MWK (Ministerium für Wissenschaft, Forschung und Kunst Baden-Württemberg) (2018). “Baden Württemberg fördert Reallabore”. Available at: https://mwk.baden-wuerttemberg.de/de/forschung/forschungspolitik/wissenschaft-fuer-nachhaltigkeit/reallabore/ [12.08.2020].

Open Knowledge International (2020). “What is Open?”. Available at: https://okfn.org/opendata/ [12.08.2020].

Pickel, S., Pickel, G., Lauth, H. J. and Jahn, D. (Eds.) (2009) Methoden der vergleichenden Politik- und Sozialwissenschaft: Neue Entwicklungen und Anwendungen. Berlin: Springer.

Raby, F. (2008). “Critical Design”. In: Erlhoff, M. and Marshall, T. (Eds.) (2008). Wörterbuch Design: Begriffliche Perspektiven des Design, 80–32. Basel: Birkhäuser.

RBS (Robert Bosch Stiftung) (2020). “Spielraum – Urbane Transformationen gestalten”. Available at: https://www.bosch-stiftung.de/de/projekt/spielraum-urbane-transformationen-gestalten [12.08.2020].

Ruby, I. and Ruby, A. (Eds.) (2008) Urban Transformation. Berlin: Ruby Press.

Scalin, N. and Taute, M. (2012). The Design Activist’s Handbook: How to Change the World (or at Least Your Part of It) with Socially Conscious Design. Palm Coast, FL: HOW Books.

Schneidewind, U. (2014). “Urbane Reallabore – ein Blick in die aktuelle Forschungswerkstatt”. Planung neu denken Online. Available at: https://d-nb.info/1064498248/34 [12.08.2020].

Schneidewind, U. (2018). Die Große Transformation: Eine Einführung in die Kunst gesellschaftlichen Wandels. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer.

Schneidewind, U. and Singer-Brodowski, M. (2014). Transformative Wissenschaft: Klimawandel im deutschen Wissenschafts- und Hochschulsystem. Marburg: Metropolis.

Schönfeld, H. (2020) Urban Transformation Design. Grundrisse einer zukunftsgewandten Raumpraxis. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Schwandt, M. (2010.) Kritische Theorie: Eine Einführung. Stuttgart: Schmetterling.

Simon, H. A. (1996). Sciences of the Artificial. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

Simonsen, J. and Robertson, T. (2013). Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design. London: Routledge.

Sommer, B. and Welzer, H. (2014). Transformationsdesign: Wege in eine zukunftsfähige Moderne. München: oekom.

Sorkin, M. (2009). “The End(s) of Urban Design”. In: Krieger, A and Saunders, W. S. (2009). Urban Design, 155–182. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota.

Stroh, D. P. (2015). Systems Thinking For Social Change: A Practical Guide to Solving Complex Problems, Avoiding Unintended Consequences, and Achieving Lasting Results. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green.

Tharp, B. M. and Tharp, S. M. (2018) Discursive Design: Critical, speculative, and Alternative Things. Cambridge, MA: Design Thinking, Design Theory.

von Borries, F. (2016). Weltentwerfen: Eine politische Designtheorie. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

WBGU (Wissenschaftlicher Beirat der Bundesregierung Globale Umweltveränderungen) (2011) Welt im Wandel: Gesellschaftsvertrag für eine Große Transformation. Berlin: WBGU.

WBGU (Wissenschaftlicher Beirat der Bundesregierung Globale Umweltveränderungen) (2016) Der Umzug der Menschheit: Die transformative Kraft der Städte. Berlin: WBGU.

Wieck, K. and Giseke., U. (2018). “Urban-rurale Verknüpfungen entwerfen”. In: Langner, S. and Frölich-Kulik, M. (Eds.) (2018). Rurbane Landschaften. Perspektiven des Ruralen in einer urbanisierten Welt, 363–384. Bielefeld: transcript.

[1] for The Great Transformation see 3.1

[2] There is no common understanding of the term urban design(er) (Krieger 2006a, b). Urban design, for me, is an extended, holistic, problem- and application-oriented transdiscipline, dealing with the design of human settlements under the complex challenges of the 21st century. “Urban designers”, in turn, for me describes the multitude of civil, scientific, municipal, political and private actors who relatively consciously and intentionally contribute to the co-production of urban spaces and processes.

[3] Land*Stadt Transformation gestalten is a transdisciplinary research project funded by the program Spielraum – Urbane Transformationen gestalten of the Robert Bosch Stiftung from 2017 to 2021 (RBS 2020). Based on the fact that urban transformational research either (and mostly) focusses on the city or (less) the countryside and the hypothesis that this dualistic cityism is one main reason for current transformation requirements and obstacles, the project aims at developing the new approach of the so-called "transformative cell” (LSTG 2020).

BB2040

[EN] Berlin Brandenburg 2040 was initiated by the Habitat Unit in cooperation with Projekte International and provides an open stage and platform for multiple contributions of departments and students of the Technical University Berlin and beyond. The project is funded by the Robert Bosch Foundation.

[DE] Berlin Brandenburg 2040 wurde initiiert von der Habitat Unit in Kooperation mit Projekte International und bietet eine offene Plattform für Beiträge von Fachgebieten und Studierenden der Technischen Universität Berlin und darüberhinaus. Das Projekt wird von der Robert Bosch Stiftung gefördert.