INFRASTRUCTURE! Thesis

What goes around comes around

By: BB2040 Editorial Team

With contributions from: FAKT, Living Systems, Edouard Barthen & Tino Imsirovic, Thierry Nolmans & Solveigh Paulus, Ziwei Dong, David Freeman, Luzie Michaels, Pascal Müller, Arina Rahma & Huizi Zhu, Sasha Amaya, Lisa Biermann, Adi Cohen, Yagmur Durak, Liujun Chen, Anna Markušina, Jonas Möller & Azada Taheri, Klub Kanal

Published on June 26, 2021

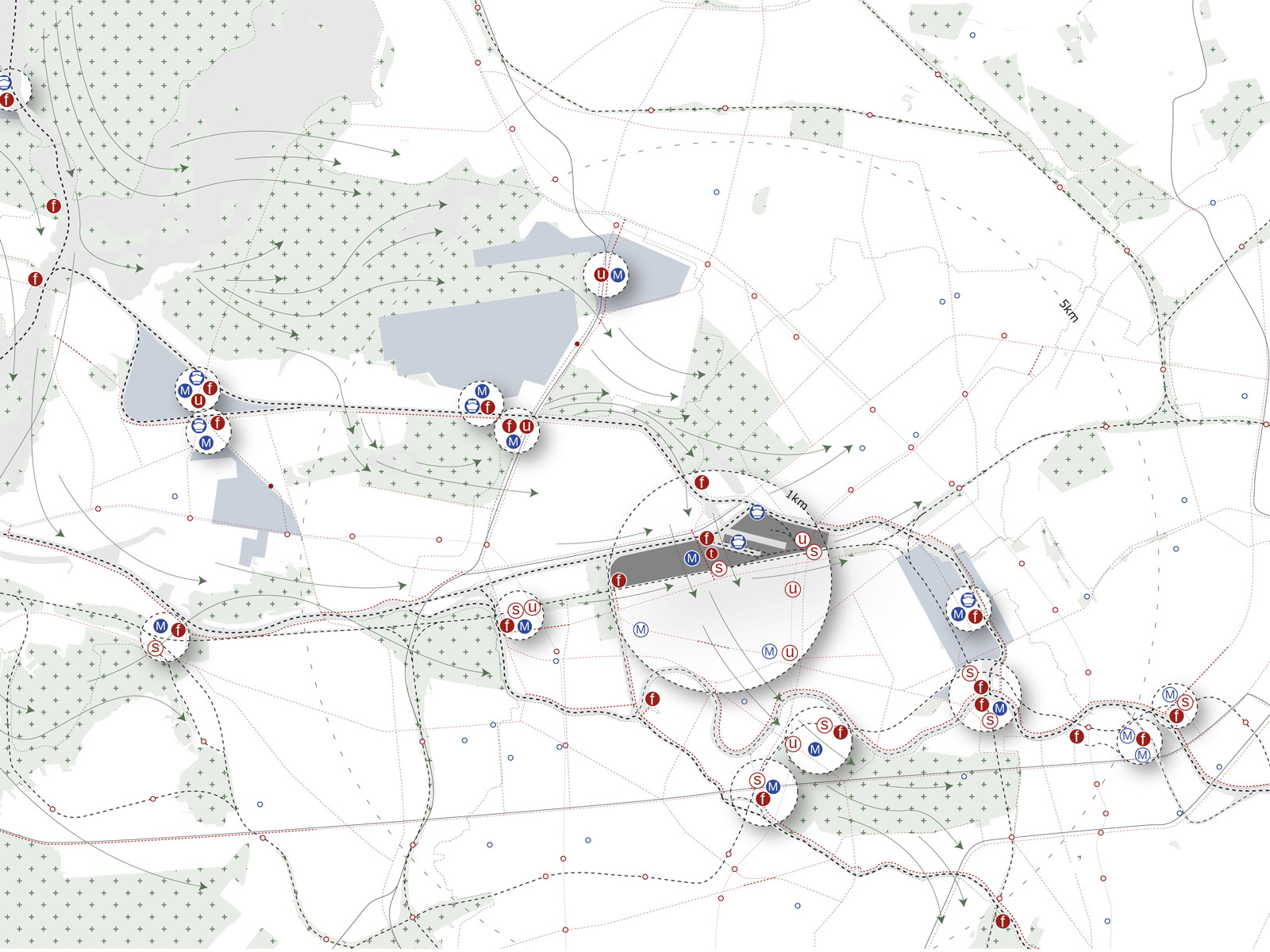

BB’s economy today is based on consumption, with sites of production and disposal connected through global logistics infrastructures exploiting human and natural resources out of sight. However, BB has a tradition of local circularity – a century ago, visionary planners imagined a city and region nourishing each other. The ground of Brandenburg once built the city of Berlin – its mud used for bricks and its sand for cement. And after the war, rubble was returned to the earth to form modest peaks around the city. The BB of the future is planned today and we must consider its life cycle from cradle-to-cradle – do Brandenburg’s forests have the answer?

The BB2040 Editorial team is formed by Philipp Misselwitz, David Bauer, Kriti Garg, Rosa Pintos Hanhausen, Simon Warne & Johanna Westermann.

This INFRASTRUCTURE! Thesis is presented at the Wissensstadt Berlin 2021 exhibition.

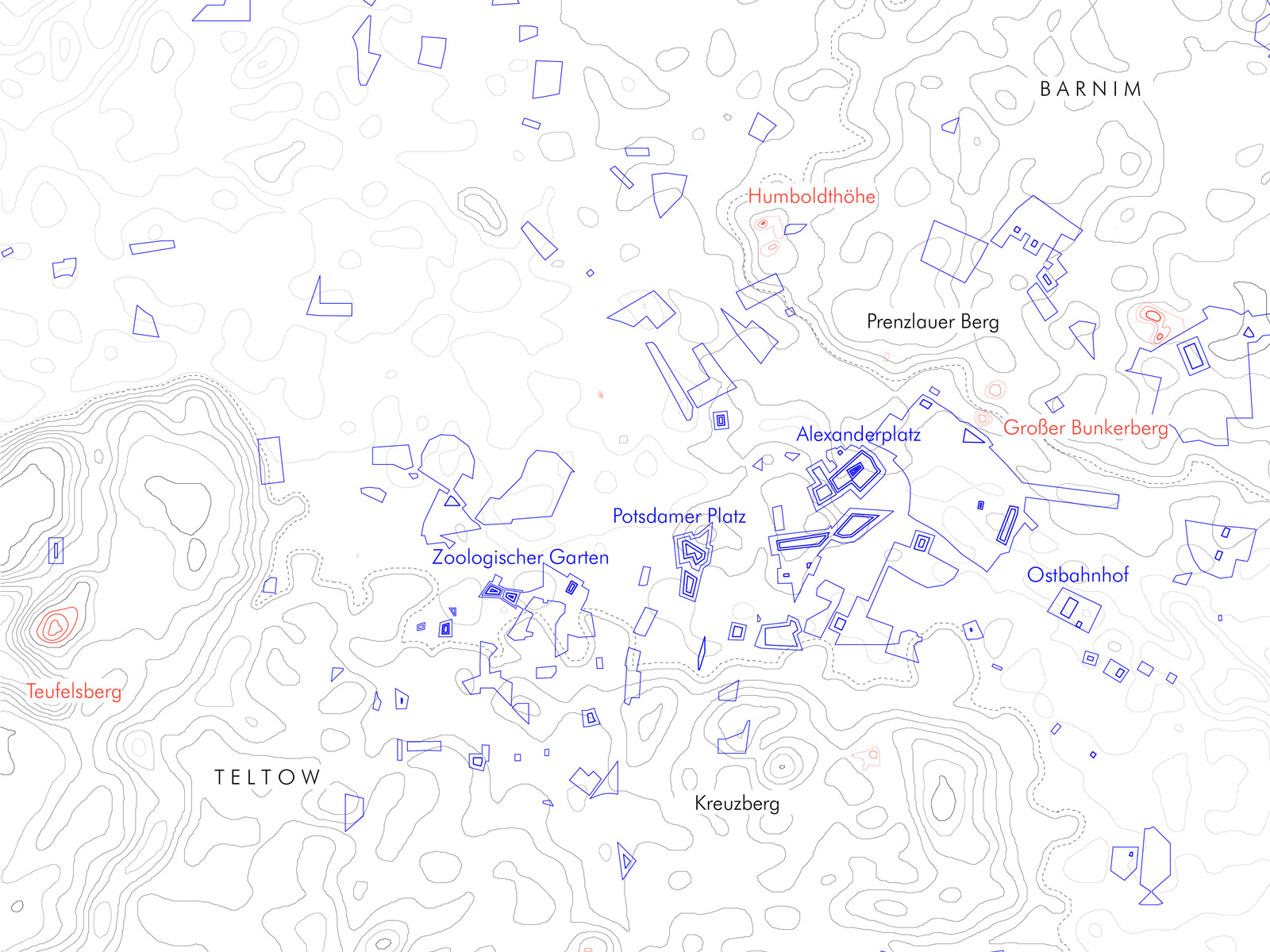

Red bricks from Brandenburg’s clay soils were the substance from which the emerging 19th century metropolis of Berlin was built. They were fired in the furnaces of kilns, such as in Zehdenick, shipped along canals and rivers, and distributed via markets on the riverbanks. After the end of WWII, 75 million cubic meters of rubble of destroyed buildings were heaped up to form artificial hills – so-called Trümmerberge – which remain key features of the city’s anthropogenic topography [1].

In the following decades, sand and cement from Brandenburg helped to reconstruct the Eastern half of the divided city into the capital of the GDR. Almost 50% of the GDR’s prefabricated concrete panels were produced, fabricated, and built in Berlin (East) and Brandenburg [2]. Many of the GDR-era prefabricated concrete panels have now been upcycled into completely new buildings [3], or join other construction waste on the still growing, albeit more moderately shaped hills around the city’s perimeter.

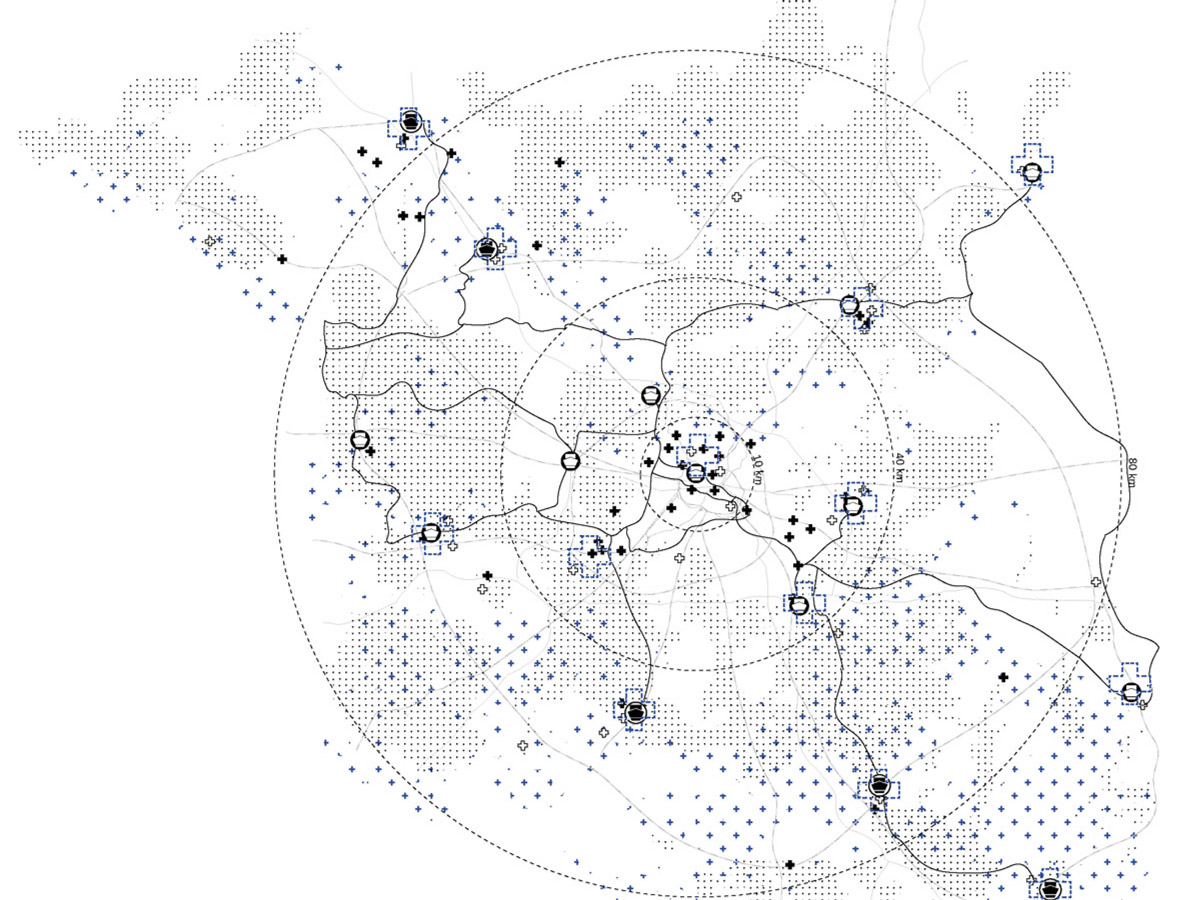

But today’s material flows including sourcing, production and disposal sites have become much more global. With global awareness of the ecological cost on the rise, and many countries becoming less willing to accept the polluting externalities of other nations’ consumption habits – Berlin-Brandenburg will need to revert back to more local, yet less resource depleting management of material cycles. Already 100 years ago, urban thinkers and planners like Migge and Wagner envisioned a circular city in material harmony with its surrounding countryside, particularly in terms of nutrients and agriculture. Although the subsequent intensification of linear industrial practices and wasteful and polluting consumption habits contaminated the landscape and scuppered the realisation of such visions, they have gained surprising currency today.

They represent uncomfortable mirrors to our unreflective, throwaway society relying on oversized logistic centres and sprawling asphalt highways to import goods, and soon after export the remaining waste out of sight. Germany exports 24.3 million tonnes of trash per year [4], supposedly to be recycled according to EU standards and largely ignorant of actual waste practices. If export routes of waste were to close tomorrow, Berlin would soon accumulate a mountain range that could make BB compete with the Alps for winter sports.

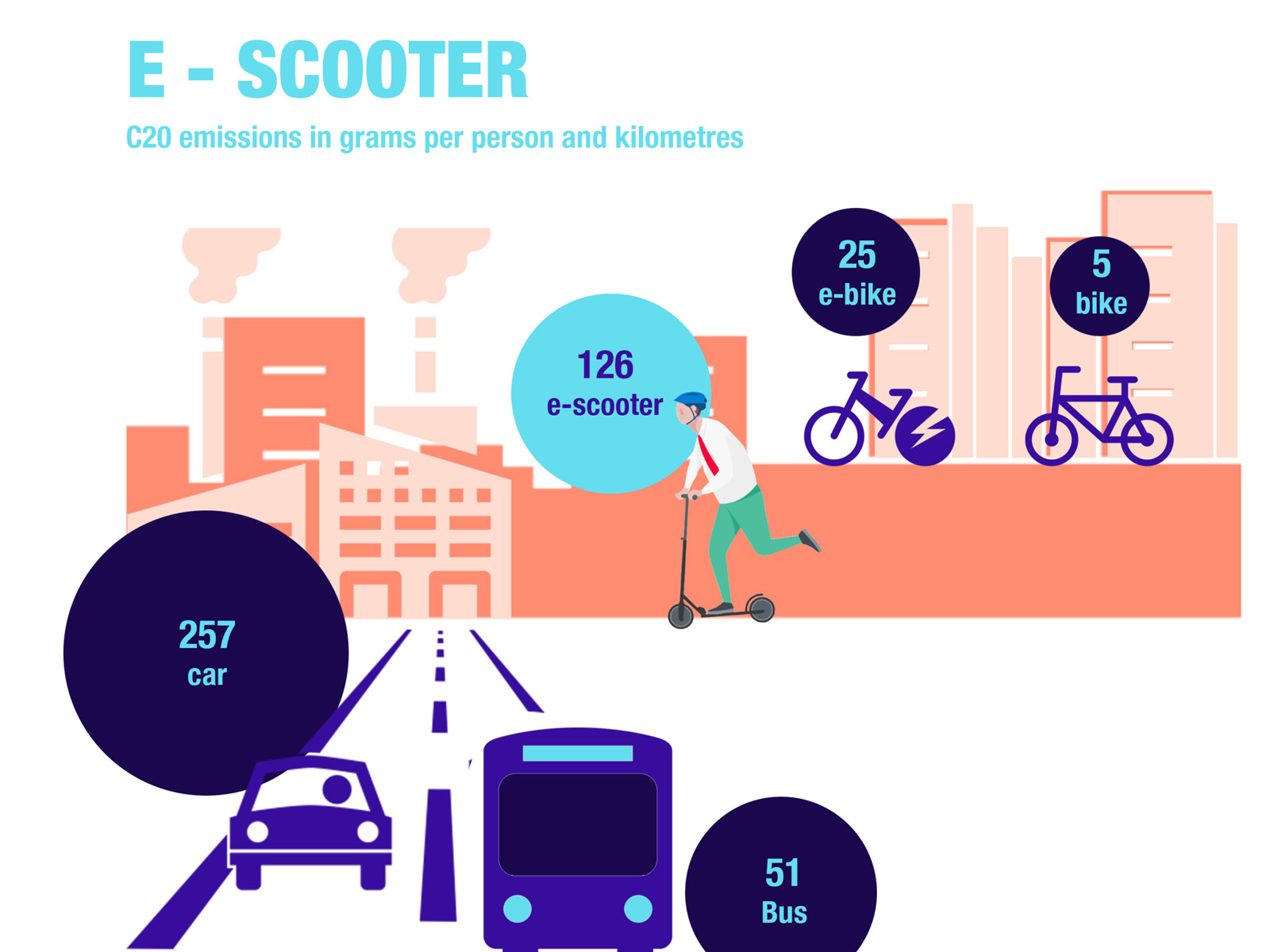

While sufficiency will be key to transitioning to a low-resource-extraction society, the reimagining of infrastructures will also require technological inputs and some material investment. As throwaway e-scooters show, relying on trial and error, or the self-regulating dynamics of the market, bears risks and requires time we no longer have.

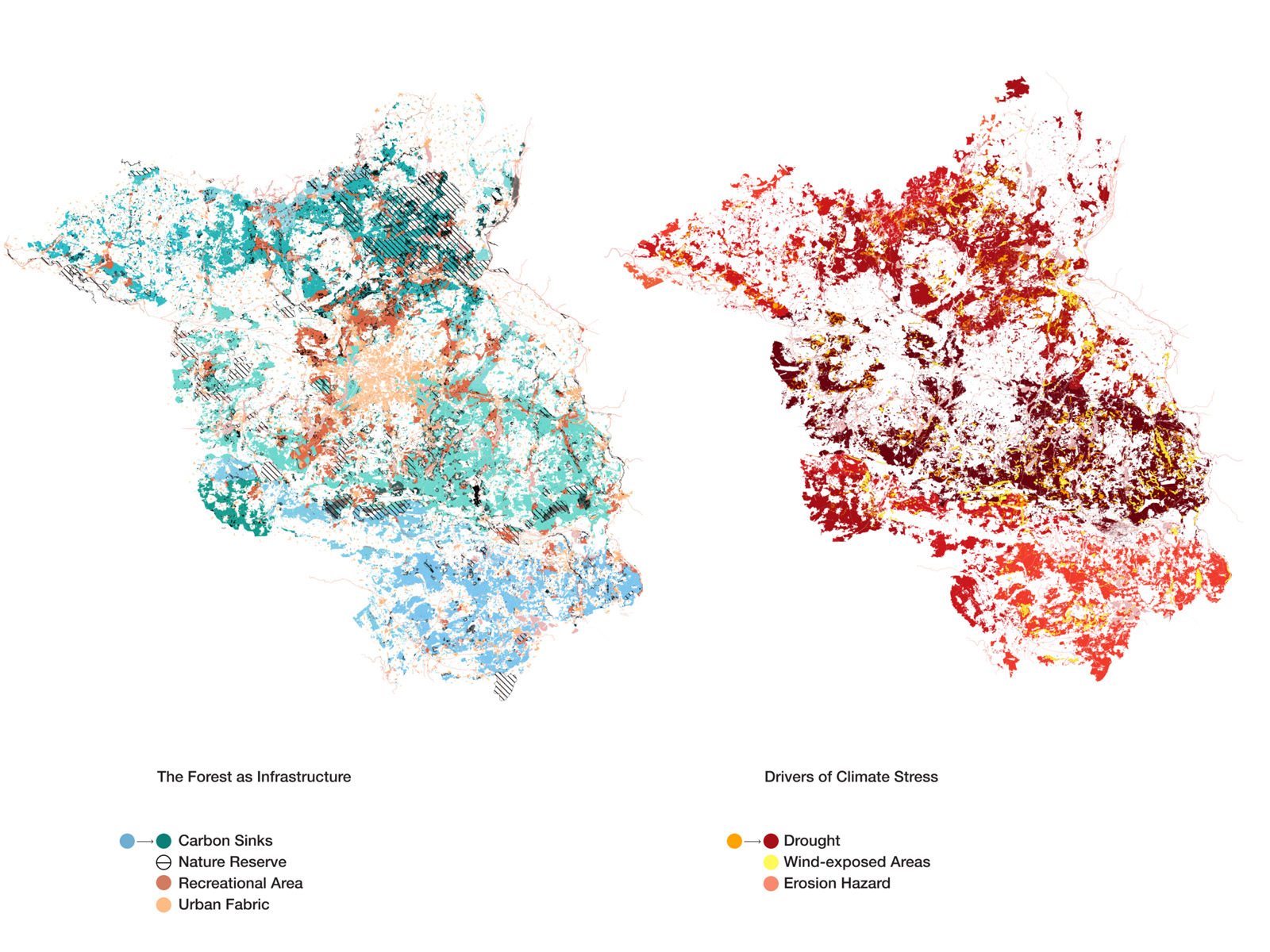

When re-imagining the infrastructures we should disentangle ourselves from the fossil fuel economy and rely on a more circular and regenerative building culture whose elements can be found above, rather than below the earth’s surface. Trees for instance have the capability to absorb CO2 as they grow. Timber construction methods could help to crush the devastating environmental footprint caused by cement and store that CO2 in long-lasting buildings. Entire cities could turn into large carbon sinks. However, our forests are also a finite resource and wood harvesting needs to be accompanied by sustainable forestation.

Berlin’s history might also offer clues towards imagining a sustainable resources region and manufacturing products can, to a large extent, be localised and decentralised as part of regional supply chains and circular economic systems which integrate material efficiency, reuse, and recycling. But the answer almost certainly lies not in technological ‘fixes’ but in transforming our habits and the logics of the consumerist economy, as well as the infrastructures that reinforce it – possibly a far greater and more complex challenge than changing how we build.

[1] Arnold, A. M. Bruchstücke - Trümmer, Bahnen und Bezirke: Berlin 1945 bis 1955. Selbstverlag, Berlin: 1999 pp. 14

[2] Schmidt, Stefan. “Jedem eine Wohnung” – Partizipationsmöglichkeiten der DDR-Bevölkerung am Beispiel

der Wohnungspolitik der SED in den 1970er Jahren”. Hallische Beiträge zur Zeitgeschichte: 2008

[3] De Graaf, Reinier. “Architektur ohne Eigenschaften”. Four Walls and a Roof. Harvard Press, USA: 2017 pp. 31-53

[4] https://www.nabu.de/umwelt-und-ressourcen/abfall-und-recycling/26205.html

BB2040

[EN] Berlin Brandenburg 2040 was initiated by the Habitat Unit in cooperation with Projekte International and provides an open stage and platform for multiple contributions of departments and students of the Technical University Berlin and beyond. The project is funded by the Robert Bosch Foundation.

[DE] Berlin Brandenburg 2040 wurde initiiert von der Habitat Unit in Kooperation mit Projekte International und bietet eine offene Plattform für Beiträge von Fachgebieten und Studierenden der Technischen Universität Berlin und darüberhinaus. Das Projekt wird von der Robert Bosch Stiftung gefördert.