INFRASTRUCTURE! Thesis

Not just cute, also vital

By: BB2040 Editorial Team

With contributions from: Sarah Schmidt, BB2040 Editorial

Published on June 26, 2021

Did you know that cities can be hives of biodiversity, and that, due to its unique history of separation, Berlin is a prime example? Through infrastructures and their flows of humans and goods, we have transported species across continents, simultaneously disrupting and enriching endemic habitats. However, the city’s biodiversity is under threat with more and more paved surfaces and harsher environments. In Brandenburg, landscapes are already highly manicured through human centered land use with industrialized methods of agriculture and forestry, which eliminate natural habitats and retreats for animals and plants.

How can we sustain biodiversity in the future?

The BB2040 Editorial team is formed by Philipp Misselwitz, David Bauer, Kriti Garg, Rosa Pintos Hanhausen, Simon Warne & Johanna Westermann.

This INFRASTRUCTURE! Thesis is presented at the Wissensstadt Berlin 2021.

Infrastructure from the Perspective of Other Species

Biodiversity refers to the variety of and symbiosis between different life forms and species such as plants, insects, animals, bacteria or fungus. Biodiversity has “utilitarian values including the many basic needs that humans obtain from it such as food, fuel, shelter, and medicine. Furthermore, biodiversity builds ecosystems which in turn provide crucial services such as pollination, seed dispersal, climate regulation, water purification, nutrient cycling, and control of agricultural pests”[1]. So overall, their interactions form resilient and healthy ecosystems. One example of positive effects of high biodiversity is the lower susceptibility of pests and diseases often found amongst homogenous planting in urban and non-urban regions.

What can a biodiversity perspective add to infrastructure? The relationship is closer than we think. Infrastructure can negatively impact biodiversity by encroaching on, dissecting or destroying natural habitats. But infrastructure can also change it in surprising ways. Trains, cars, planes and even ships transport not only people and goods but also insects, critters, wildlife, pollen and seeds to new and alien habitats. This can facilitate the invasion of invasive species (such as the Asian Buchsbaumzünsler) with dramatic effects, but also lead to the increase in diversity and ultimately the strengthening of biodiversity hubs.

Industrialization of the countryside, with its large agricultural farms and forest plantations, the rise of monocultures, the disappearance of wetlands and the increasing sealing the surfaces, with it’s buildings and infrastructure is displacing high numbers of species [2]. These disturbances through land cultivation procedures as well as noise and chemical pollution by overuse of chemical pesticides is depriving many species of nutrition and living habitats. And at the brink of extinction [3]—harsher and unpleasant environments of the countryside force many species to search for refuge zones within the city, where they find an abundance of food and shelter within unique new ecological niches.

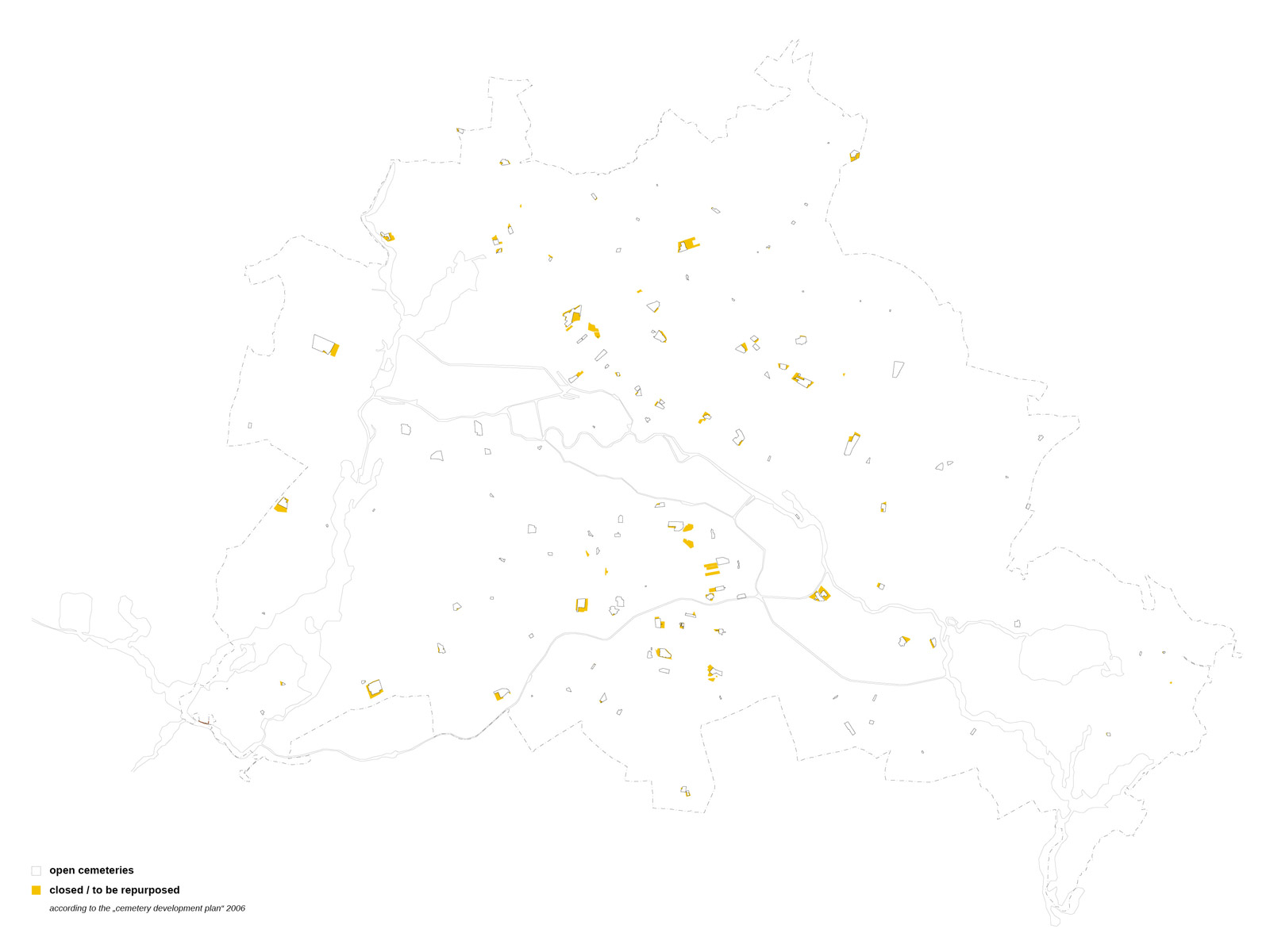

Typologies of Urban Wilderness

Particularly during the pandemic, Berlin’s infrastructure of generous parks, forests and inner-city lakes received tremendous re-appreciation providing outdoor relief during lockdown. But more precious and biodiverse are often the places we don’t care about. Old industrial areas, rail yards, wastelands, decommissioned military sites and similar spots provide refuge for many threatened species that not only had to flee from a disruptive countryside, but also are too shy to co-inhabit the city with humans. Berlin’s history of wartime destruction, partition and economic collapse after 1990 generated a unique landscape of wastelands, urban fringes, urban wastelands and interstitial spaces. This scared and fragmented urban landscape, together with green and blue elements and a large variety of low to high-rise building typologies, allows for the emergence of a protected heterogeneous environment that hosts various life forms, unique ecosystems and flourishing biodiversity hubs. Research suggests that “twice as many foxes per square meter now live in Berlin than in German forests”[4]; with cemeteries being a unique intersection between park infrastructure and biodiversity hubs.

Ecologists believe that planning and accessibility to urban wilderness as an experience within cities is also key in building societal support and momentum for more conservation of nature and biodiversity in general [5]. These are the spaces within the city that must be made accessible, curated with paths and benches to evoke emotions and solidarity with nature and biodiversity amongst city dwellers, which then can be transferred again to larger landscapes and forest regions outside of the city. Yet, rather than clinging to a traditional—and outdated— conception where biodiversity is a quality of the countryside, we will need to accept the reality of urban areas as key biodiversity hubs; ecosystems where native and alien species coexist in symbiosis to overcome the adversities of climate change and urban pressures (Urban Wilderness).

Challenges for Infrastructure Planning

The challenge for infrastructure in the coming decades is to welcome biodiversity into the cities: to go beyond an aestheticization of nature but rather to consider urban green and blue elements as essential living habitats. Protecting existing interstitial spaces as refuge alone will not be enough. The redesign of infrastructure should also include to reduce their disruptive and barrier-like impact on urban ecology. Green bridges over highways which connect and create migration corridors for many species whose routes are disrupted by the fast speed highway infrastructure could also be adopted within cities. Moreover, infrastructures will need to be thought of as multi-functional systems, which not only provide a single service to humans but rather also create habitats within its sheer volume for biodiversity to live in and traverse through. Infrastructural design and planning should follow a system-oriented approach strengthening co-evolution between all species, human and non-human.

[1] Biodiversity. Urban Blue Grids. Atelier GroenBlauw. https://www.urbangreenbluegrids.com/biodiversity/ [Accessed 10.06.21]

[2] What is Biodiversity? American Museum of Natural History. https://www.amnh.org/research/center-for-biodiversity-conservation/what-is-biodiversity [Accessed 10.06.21]

[3] Kowarik I. et.al. (2013) Prevalence of alien versus native species of woody plants in Berlin differs between habitats and at different scales. Technische Universität Berlin, Berlin-Brandenburg Institute of Advanced Biodiversity Research. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236208484 [Accessed 10.06.21]

[4] (2020) Sixth Mass Extinction of Wildlife Accelerating- Study. Africa America Asia Europe Oceania. Earth.org. https://earth.org/sixth-mass-extinction-of-wildlife-accelerating/ [Accessed 10.06.21]

[5] What is Biodiversity? American Museum of Natural History. https://www.amnh.org/research/center-for-biodiversity-conservation/what-is-biodiversity [Accessed 10.06.21]

BB2040

[EN] Berlin Brandenburg 2040 was initiated by the Habitat Unit in cooperation with Projekte International and provides an open stage and platform for multiple contributions of departments and students of the Technical University Berlin and beyond. The project is funded by the Robert Bosch Foundation.

[DE] Berlin Brandenburg 2040 wurde initiiert von der Habitat Unit in Kooperation mit Projekte International und bietet eine offene Plattform für Beiträge von Fachgebieten und Studierenden der Technischen Universität Berlin und darüberhinaus. Das Projekt wird von der Robert Bosch Stiftung gefördert.