INFRASTRUCTURE! Thesis

It won't just

blow over

By: BB2040 Editorial Team

With contributions from: BB2040 Editorial Team

Published on June 26, 2021

Air knows no borders, and neither does airborne pollution and heat. Berlin, built from thermally-massive materials, is already up to 7°C warmer than the surrounding landscapes of Brandenburg due to the urban heat island effect [1]. Global heating has to be tackled on all levels, including new mitigation infrastructures for carbon capture and storage, and the prioritization of environments that can sequester carbon from the air. At the same time, we must learn to adapt to heat by mobilizing cooling infrastructures which utilize water and inner-city greenery, and let air flow.

The BB2040 Editorial team is formed by Philipp Misselwitz, David Bauer, Kriti Garg, Rosa Pintos Hanhausen, Simon Warne & Johanna Westermann.

This INFRASTRUCTURE! Thesis is presented at the Wissensstadt Berlin 2021.

Air is all around us. We frequently talk about it. But how aware are we of our impact on it? Weather observation has somewhat become a societal obsession fed by more readily available apps on our smartphones to tell us how hot, humid, windy, and even how polluted air is. While we yearn to understand trends or underlying patterns and equip our cities and landscapes with sensors to better forecast and predict weather developments, our ignorance towards the most important facts remains blatant: humans themselves are to blame for the weather becoming more extreme and unpredictable.

In our cities, air is getting hotter due to the high amount of building mass that stores heat from the sun during the day and emits it back into the air at nighttime. Known as the heat island effect, we make this phenomena worse by densifying the city, developing vacant land, reducing and paving greenscapes and by letting our lakes and streams dry out. Destroying the natural cooling infrastructures of our cities sets up a disastrous chain reaction. The lowering of groundwater tables, the drying up of soils, forest degradation and finally, also dryer and hotter air and less rain for the overall region. Additionally, air is also getting more polluted through the spread of microplastics, exhaust fumes from various sectors and industries such as energy, mobility, agriculture, or waste, with serious health impacts. Yet air affects not just the health of our bodies, but also the health of ecosystems and the dangerously changing constitution of the atmosphere fueling climate change.

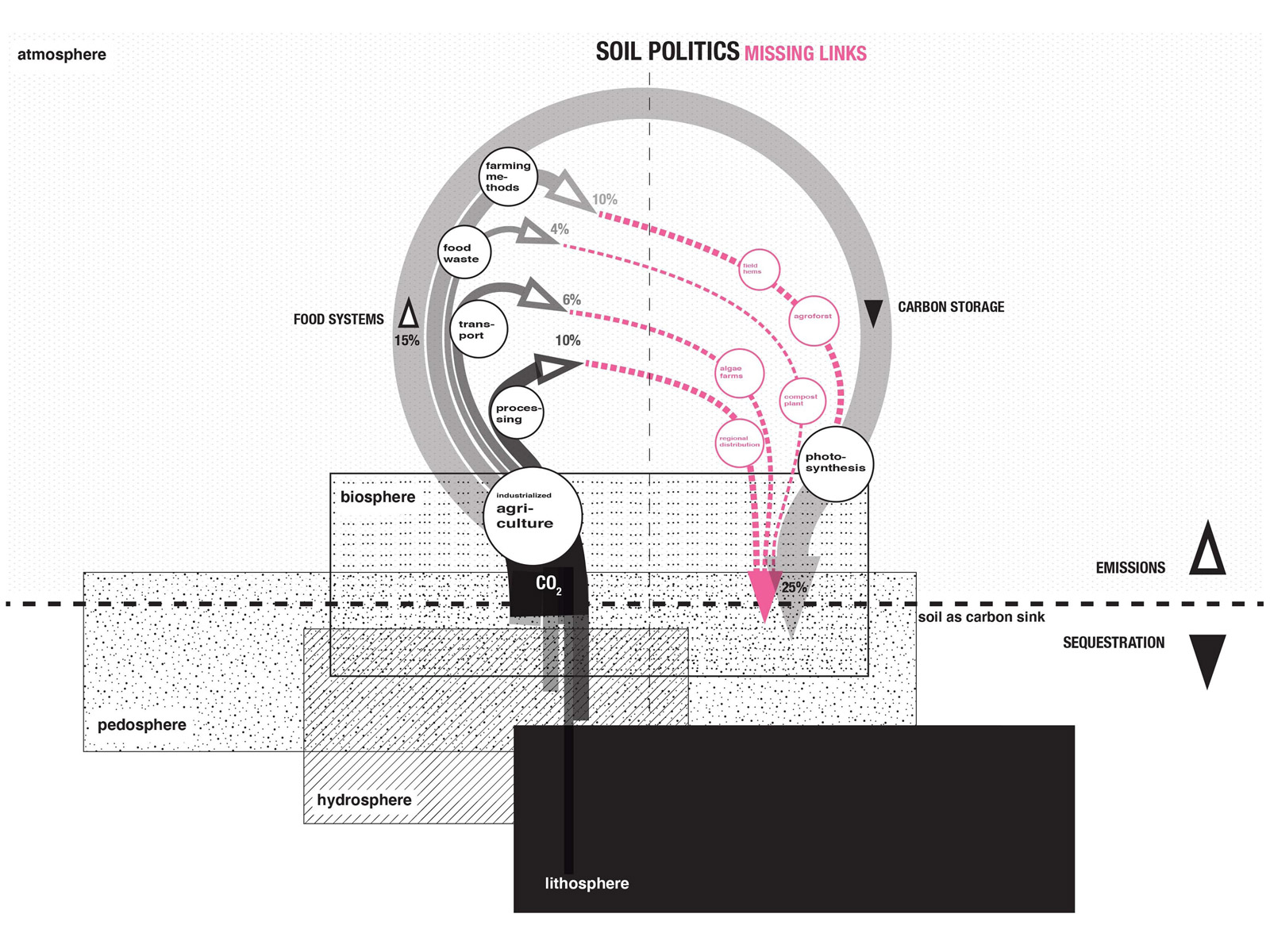

Living in the Anthropocene [2], where human impact on Earth is so vast and irreversible that they literally call it the ‘era of the human being’ leads some to believe that climate engineering or geo-engineering is the only answer, hoping that advanced technology will pull out excess carbon from the atmosphere, mineralize it and store it back underground or even underwater [3]. Yet, effective and affordable technological fixes may never become available, and, if found, might disrupt natural systems even further. Rainforests, soils and oceans are vital if we are to strive for co-evolution and balanced synergies with our natural carbon sinks. But we are currently destroying them through deforestation, industrial agriculture and fishery.

In the 21st century, air has become the global community's biggest governance challenge. As an element without borders, responsibility to protect it cannot easily be pinned to nation states. While Germany managed to tackle the issue of acid rain in the 1980s by regulating industrial exhaust fumes through the introduction of new exhaust filters for factories and power plants within the energy sector [4], many other air polluters remain unregulated. For example, the agricultural and waste economies created and fueled by our own daily and dietary habits are polluting the air on just as large a scale as the energy sector of the 1980s; with methane, nitrogen dioxide and many other gases released daily into the air by the industrial farming industry.

In Berlin-Brandenburg, the trans-local interdependencies across various scales can be felt very directly: dust created in drought areas of Brandenburg is carried with the wind across the region, and in extreme weather instances, even mixing with particles carried from other parts of Europe or northern Africa. The same wind also picks up microplastic particles, created with every rotation of the wheel in our daily car use. Both these and many other sources of particulate pollution, especially from car and factory exhausts are leading to health problems such as respiratory illnesses and more premature deaths, not just for high-risk groups and the elderly, but are also becoming a health crisis for every urban dweller.

With global warming, extreme weather conditions, air pollution, and, most recently, also the battle against airborne viruses, our societies will need to act collectively.

Air should be considered a global commons resource. Efforts to protect air and limit pollution must therefore be transnational, based on globally negotiated mitigation plans. Planetary guardrails can only be achieved through effective regulations, strategic investment to fuel a transformation of our economies and, perhaps most importantly, a broad societal awareness encouraging a change of habits and lifestyles. We could think of these combined measures as a network of air-protecting infrastructures.

Transformative action is particularly urgent in the built environment. Reducing energy intensive cooling systems and improving passive and active ventilation systems can contribute to cleaner and cooler outdoor air and better health. Making buildings less reliant on indoor ventilation also prevents the spread of viruses such as COVID-19, or high CO2 concentrations that can trigger fatigue, hamper comfort and productivity and fuel illness.

Developing urban green and blue infrastructures consisting of urban parks, forests, wastelands or water bodies already play a vital role in cooling the city. These could be extended by new spatial typologies such as streets—freed from car surfaces could be unsealed and greened—and more green roofs or green façade networks. Additionally, with the rise of commercial and surveillance drones, air activities in urban areas needs to be regulated to ensure the survival of living organisms relying on air for their daily routine and survival. It is our task as citizens, architects, planners, urbanites, investors or politicians to push for a symbiotic planning where human and natural systems are thought of together to protect one of the most basic conditions of planetary survival: air.

[1] Lauf, S. et.al. (2015) Urban climate and heat stress patterns in Berlin,Germany. ICUC9 - 9th International Conference on Urban Climate, 12th Symposium on the Urban Environment. http://www.meteo.fr/icuc9/LongAbstracts/poster_26-12-7421601_a.pdf [Accessed 25.06.21]

[2] Anthropocene. Encycopedic Entry. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/anthropocene/ [Accessed 25.06.21]

[3] Fleming, A. (2021) Cloud spraying and hurricane slaying: how ocean geoengineering became the frontier of the climate crisis. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/jun/23/cloud-spraying-and-hurricane-slaying-could-geoengineering-fix-the-climate-crisis [Accessed 25.06.21]

[4] Grefe, C. (2021) Neue Bäume braucht das Land. Naturschutz. Die Zeit. https://www.zeit.de/2021/17/naturschutz-waldsterben-baeume-saurer-regen-oekokrise [Accessed 25.06.21]

BB2040

[EN] Berlin Brandenburg 2040 was initiated by the Habitat Unit in cooperation with Projekte International and provides an open stage and platform for multiple contributions of departments and students of the Technical University Berlin and beyond. The project is funded by the Robert Bosch Foundation.

[DE] Berlin Brandenburg 2040 wurde initiiert von der Habitat Unit in Kooperation mit Projekte International und bietet eine offene Plattform für Beiträge von Fachgebieten und Studierenden der Technischen Universität Berlin und darüberhinaus. Das Projekt wird von der Robert Bosch Stiftung gefördert.