INFRASTRUCTURE! Thesis

Do infrastructures even care?

By: BB2040 Editorial Team

With contributions from: Christoph Muth & BB2040 Editorial Team

Published on June 26, 2021

Food banks, childcare, public toilets, the Corona Warn-App, food delivery services and emergency shelters are just some examples of Infrastructures of Care. Self-care, care-for-others, solidarity, kinship, care in society, the provision of shelter, security and support; or the provision of a safe future for coming generations are all different types of care. Care can be defined in a multitude of different ways, but essentially comprises the provision of what is needed for health, welfare, maintenance, and protection.

Germany, with a median population age of 46 years [1], is one of the oldest countries globally. Without access to broadband, good train connections, and amenities such as alternative Kindergartens, parts of rural Brandenburg will seem to age more rapidly than the vibrant inner city of Berlin. Our infrastructures will have to serve the demands of old age, while ageing at the same time themselves – needing to adapt to new logics of care, with drastic spatial and societal implications.

The BB2040 Editorial team is formed by Philipp Misselwitz, David Bauer, Kriti Garg, Rosa Pintos Hanhausen, Simon Warne & Johanna Westermann.

This INFRASTRUCTURE! Thesis is presented at the Wissensstadt Berlin 2021 exhibition.

On a good day we could say that infrastructures take care of us. They are made to deliver care; they are what bind strangers together into societies, providing for them day-to-day, forming social networks and social institutions. Many infrastructures are older than individuals – taking care for decades or even centuries, reassuring us with their presence, without needing to constantly be renegotiated from the bottom-up.

On a bad day however we may notice that infrastructures only take care of those with access to them. Debates circling around public spending divide people on whether societal infrastructures provide sufficient care for current and upcoming challenges or simply waste too much tax money to allow individuals and the economy to prosper.

Infrastructures of care tend to be built when a critical mass is excluded from other infrastructure – social housing, homeless shelters, and even allotment gardens emerged due to widespread poverty. But infrastructures of care on a larger scale are generally only built once it has become politically untenable to do anything except provide them. Until that point, it is down to individuals and non-governmental organisations to provide care.

Normative frameworks to guide transformation to sustainability processes at a global scale, such as Agenda 2030 are based on principles of inclusivity, summarised by the principle of “Leaving No-One Behind” (LNOB) [2]. While this reflects a growing global awareness of uneven development and inequities it has, so far, only been understood in an anthropocentric way.

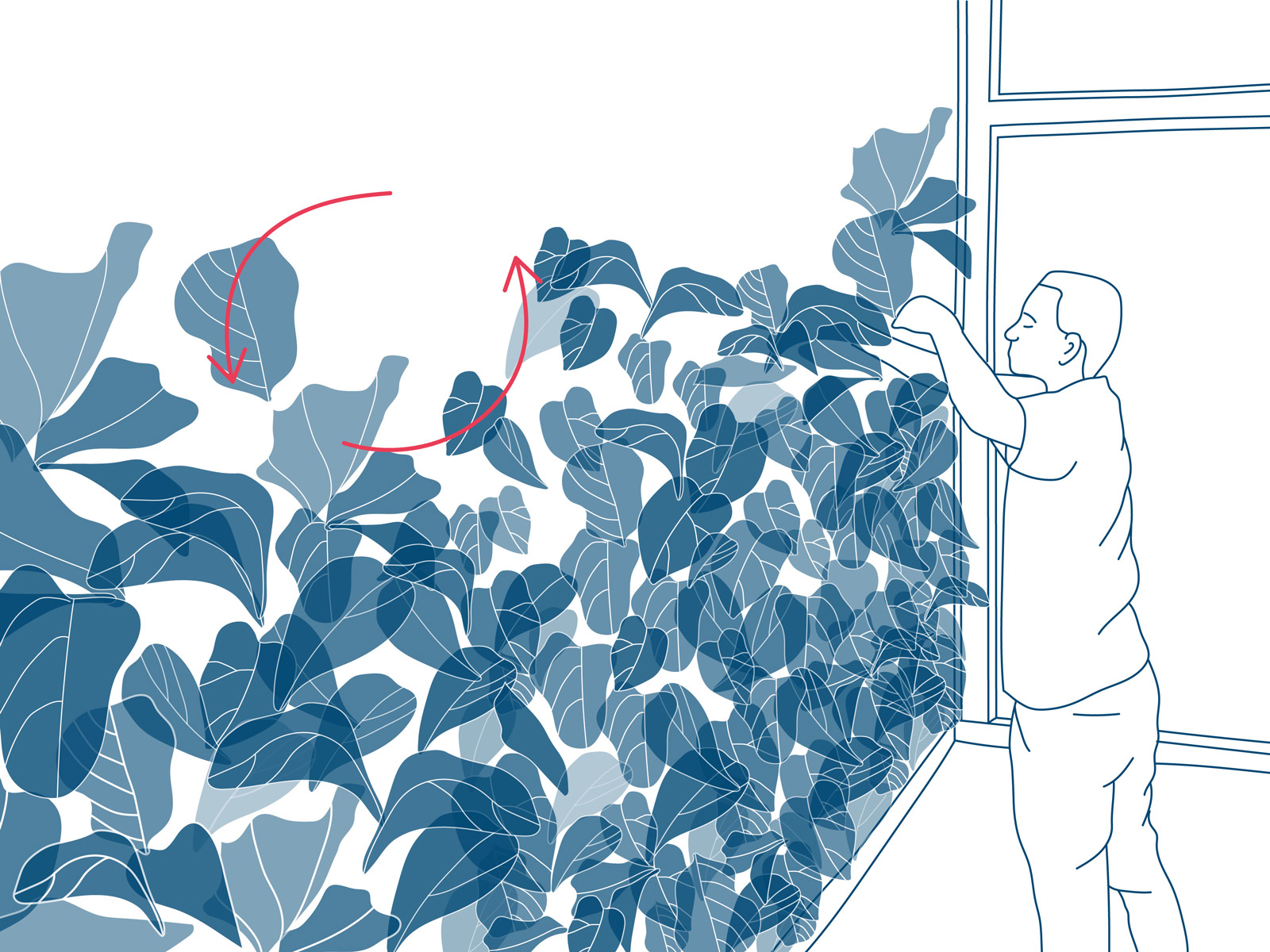

The principle of care, however, should take questions of human responsibility further. We could understand it also as caring – “doing something correctly or to avoid damage or risk” – towards the planetary system in general. Our responsibility of care in the future extends beyond our elderly relatives collapsing in hot streets or sharing our space with people from climate-ravaged zones. It is also about taking care of the finite material resources of our world as well as other, non-human beings and living things. The concept of care should be expanded to embrace the environmental system of the earth of which we are a part.

Infrastructures of this expanded vision of care will need to include environmental protection and stronger regulations of responsible use of materials. We should reduce our wasteful lifestyles, use technological gadgets and wear clothes for longer before carefully considering their disposal, or make sure other earthly creatures like insects and wild animals can thrive.

It is also an act of care to leave some things be and not smother them. In voids resulting from BB’s unique history we can see that opportunities to create anew lurk in the spaces that our economic thinking has neglected – left-behind and leftover spaces possess chances for new growth: of nature, of human creativity, of institutions of care. Where central resources and funding are low, particularly in structurally weak parts of rural Brandenburg, different actors can work together resourcefully [3] to make the most of situations with increasing scarcity of social provisions (e.g. in the case of population decreases).

As we move into the future, Infrastructures of Care will bind many of our economic and intellectual resources. Not just for accommodating an ageing society, but also in the care and maintenance of the ageing infrastructural systems we rely heavily upon, adapting and conceiving them anew for emerging challenges and for the integration of – above mere flows of humans and goods – planetary needs and other-than-humans.

Care is therefore an ethical concept as well as a call for action. It embraces both repair as well as prevention, and while tech fixes might be able to win us some battles, they might not save us from the next crisis. Smart technologies today bear great potential in not just slowing down climate change, but their convenience will also somewhat lighten the human burden when it comes to looking after an ageing society. However, with these technologies – from mass automation of our life-support systems, including of nature, eg. robotic bees, or genetic reprogramming of species to eradicate diseases and deployment of microorganisms to process our plastic waste – we need to be careful about the dependencies and externalities that are being created.

Sources

[1] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Population_structure_and_ageing

[2] https://unsdg.un.org/2030-agenda/universal-values/leave-no-one-behind

[3] MacKinnon, Danny; Driscoll Derickson, Kate 2012: “From Resilience to Resourcefulness.” Progress in Human Geography 37 (2): 253–70

BB2040

[EN] Berlin Brandenburg 2040 was initiated by the Habitat Unit in cooperation with Projekte International and provides an open stage and platform for multiple contributions of departments and students of the Technical University Berlin and beyond. The project is funded by the Robert Bosch Foundation.

[DE] Berlin Brandenburg 2040 wurde initiiert von der Habitat Unit in Kooperation mit Projekte International und bietet eine offene Plattform für Beiträge von Fachgebieten und Studierenden der Technischen Universität Berlin und darüberhinaus. Das Projekt wird von der Robert Bosch Stiftung gefördert.